Hartlepool Sports & Leisure

Hartlepool Sports & Leisure

- Cinemas, Theatres & Dance Halls

- Musicians & Bands

- At the Seaside

- Parks & Gardens

- Caravans & Camping

- Sport

Hartlepool Transport

Hartlepool Transport

- Airfields & Aircraft

- Railways

- Buses & Commercial Vehicles

- Cars & Motorbikes

- The Ferry

- Horse drawn vehicles

A Potted History Of Hartlepool

A Potted History Of Hartlepool

- Unidentified images

- Sources of information

- Archaeology & Ancient History

- Local Government

- Printed Notices & Papers

- Aerial Photographs

- Events, Visitors & VIPs

Hartlepool Trade & Industry

Hartlepool Trade & Industry

- Trade Fairs

- Local businesses

- Iron & Steel

- Shops & Shopping

- Fishing industry

- Farming & Rural Landscape

- Pubs, Clubs & Hotels

Hartlepool Health & Education

Hartlepool Health & Education

- Schools & Colleges

- Hospitals & Workhouses

- Public Health & Utilities

- Ambulance Service

- Police Services

- Fire Services

Hartlepool People

Hartlepool People

Hartlepool Places

Hartlepool Places

Hartlepool at War

Hartlepool at War

Hartlepool Ships & Shipping

Hartlepool Ships & Shipping

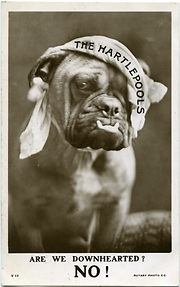

The Bombardment

08:10am until 08:50am

A general history of the bombardment of the Hartlepools by German warships in 1914. For more details see Note The Bombardment of the Hartlepools.

Related items :

Bombardment Album

Bombardment Album

This remarkable collection of postcards are from an album originally belonging to Joseph Davies, (formerly of South Road but latterly at 111 Thornton Street), which then passed to 'Uncle Jo's' nephew John Davies. Most of the postcards have captions.

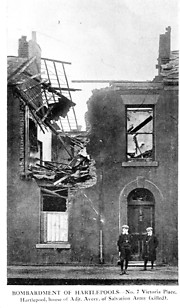

More detail » Damaged Houses

Damaged Houses

Created by unknown

Donated by Mrs. Janice Nicholson

Created by unknown

Donated by Mrs. Janice NicholsonDated 1914

Damage to houses and railway lines after the Bombardment.

More detail » Fourth Yorkshire Regiment

Fourth Yorkshire Regiment

Donated by Douglas Ferriday

Donated by Douglas FerridayPart of the Hartlepool Library Service collection

Dated 1914

The men of the Fourth Yorkshire Regiment (Green Howards) outside the Staincliffe Hotel, Seaton Carew, with the two regimental dogs and six German shells discovered after the bombardment of Hartlepool in 1914.

More detail » German medal front and reverse

German medal front and reverse

Part of the Hartlepool Museum Service collection

Part of the Hartlepool Museum Service collectionCommemoration of Bombardment

More detail » Infantry Officers with unexpoded shells

Infantry Officers with unexpoded shells

Donated by Douglas Ferriday

Donated by Douglas FerridayPart of the Hartlepool Library Service collection

Infantry Officers and sergeants outside the Staincliffe Hotel with unexploded shells from the bombardment.

More detail » SMS Blucher

SMS Blucher

Part of the Imperial War Museum collection

Part of the Imperial War Museum collectionGerman armoured cruiser which was one of three involved in the bombardment of Hartlepool. It was hit six times causing minimal damage although 9 crew members were killed and 3 were injured.

More detail » SMS Moltke

SMS Moltke

Part of the Imperial War Museum collection

Part of the Imperial War Museum collectionGerman battle cruiser which was one of three vessels which took part in the bombardment of Hartlepool in December 1914. It was hit by a coastal shell but was only slightly damaged and there were no casualties.

More detail » SMS Seydlitz

SMS Seydlitz

Part of the Imperial War Museum collection

Part of the Imperial War Museum collectionGerman battle cruiser which took part in the bombardment of Hartlepool in December 1914. It was hit 3 times by coastal battery but there were no casualties.

More detail » Shell Fragment

Shell Fragment

Donated by Kevin Wheelan

Donated by Kevin WheelanThis shell fragment is a souvenir of the German naval bombardment of Hartlepool on 16th December 1914.

The base measures 71/2 inches x 41/2 inches. The shell fragment measures 41/2 inches wide x 2 inches deep x 2 inches high.

More detail »

Shell fragment shield

Shell fragment shield

Donated by Adrian Thatcher

Donated by Adrian ThatcherThe shield was made by Adrian Thatcher's great-grandfather Robert William Graham as a memento of the German attack on The Hartlepools' on 16th December 1914. Robert lived in West Hartlepool and was an engineer by profession but he was also a volunteer member of the fire brigade. He was called that day to assist with controlling the fires and dealing with the damage. He picked up the shrapnel fragment in the course of his duties that day and subsequently made the shield whch has been passed down to his great- grandson Adrian.

More detail » The Bombardment of the Hartlepools

The Bombardment of the Hartlepools

Introduction

Three German warships attacked the twin towns of Hartlepool and West Hartlepool on the morning of Wednesday 16th December 1914. It was four and a half months after the outbreak of the First World War. The attack lasted just forty minutes, from 8:10a.m. to 8:50a.m., killing more than one hundred people and injuring many others.

Reasons for the attack

Germany had recently lost a battle with the British Navy in the South Atlantic. The Germans now needed a successful mission to boost morale at home. Germany’s intention was to attack the north-east coast of England. The Hartlepools were a good target because of their shipyards and engine works, which were important to the British war effort. Also the towns were only about 330 nautical miles across the North Sea from the small island of Heligoland, where the German Fleet was stationed (a nautical mile is equal to 1852 m, or 6076 ft). It was possible for ships to cover this distance under cover of darkness during the long winter nights.

The German mission to attack the north-east coast

A flotilla of ships was sent from Germany towards the coast. As weather conditions in the North Sea worsened, the smaller ships returned home, leaving five larger ships to complete the journey. TheDerfflinger and the Von Der Tann headed towards Scarborough and Whitby, where their shells damaged many buildings, and killed over twenty civilians. The other three ships headed towards Hartlepool.

The German ships involved in the attack on the Hartlepools

The three German ships were the battle cruisers Seydlitz and Moltke, and the older, armoured cruiser,Blucher. They had much larger guns than the defending guns on the Hartlepool Batteries. The warships fired 1150 shells (some up to 11 in., or 27 cm, in diameter) into the Hartlepools. The two coastal defence batteries on the Heugh managed to return fire with 123 shells, the largest of which was 6 in.(15 cm) in diameter.

The Hartlepools’ defences

The Hartlepool coastline was defended by four destroyers, two light cruisers and a submarine. Two gun batteries defended the towns. The Heugh Battery, originally built in 1859, had two 6-inch guns, which were installed in 1899. The Lighthouse Battery, built in 1855, was approximately 150 yards (137 m) to the south. It was originally armed with four 64-pounder guns, which were replaced in 1907 by one 6-inch gun. The Batteries were manned by 320 officers and men from the 18th Battalion of the Durham Light Infantry (the PALS), and The Durham Royal Garrison Artillery (the Territorial Army).

Events of the night before the attack

Late on the evening of 15th December, the Battery Commander received a telegram from the War Office which read:

“ A special sharp look-out to be kept all along east coast at dawn tomorrow, Dec 16th. Keep fact of special warning as secret as possible; only responsible officers making arrangements to know.

Troopers, London”

A postscript said:

“In connection with above, the Fortress Commander wishes you to take post from 7 -8.30am. If all quiet at latter hour troops may return to billets”

The special warning was received direct. Normally warnings of enemy vessels were received through the Port War Signal Station.

Events early in the morning of the attack

At 5:30 a.m. on Wednesday 16th December 1914, the four British destroyers based at Hartlepool went out as usual to patrol the coast, unaware of the warning delivered to the battery commander. By 6.30a.m., an hour before dawn, the soldiers were at their posts at the battery preparing for the day.

The morning was cold and misty with a fog bank 4,000 yards (3656 m) out at sea off the Hartlepools. As the German ships approached, they were spotted by the naval patrol, which fired on them. The German fleet was much more heavily armed, however, and the patrol boats were unable to stop them.

On land, the outlines of the three large warships became visible through the mist, about three miles (4.8 km) offshore. Lookouts at a coastal battery at South Gare, on the mouth of the River Tees, saw the ships first, but thought they were friendly because they were flying British flags. As the ships drew closer, however, these were hauled down and replaced with German flags.

The attack on the towns

At 8:10 a.m. the German warships, now only two and a half miles (4 km) off the coast, opened fire on the Headland batteries.

During the following battle, two factors counted in the towns’ favour. The first was the recent camouflaging of the Heugh Battery. A false extension caused the enemy ships to fire high, so that many of the shells missed their target. The second was that in the time between the Germans’ spying out the area and their attack, one of the buoys in the harbour had been moved nearer to the shore. This caused the German ships to come in much closer to shore than they needed, given the range of their guns.

The first shots landed close to the Heugh Battery, killing Private Theophilus Jones of the 18thBattalion D.L.I. Three other soldiers were fatally wounded at the same time. Private Jones became known as the first soldier to be killed on English soil during the First World War. Two more soldiers were killed by the next shell. This also hit the telephone line between the two batteries, so the Commander had to try to relay orders by megaphone. This proved impossible because of the noise, so a man was sent to stand between the command post and the battery to relay orders by word of mouth.

The Lighthouse Battery gun managed to hit Blucher, killing nine sailors and causing damage to the ship and two of her 6-inch guns. Following this, Blucher placed herself in such a position that the batteries were unable to fire on her because the lighthouse blocked their line of fire.

Three British coastal defence craft (two light cruisers and a submarine) were moored in the Victoria Dock at the time of the attack. The submarine was hit as it came out of the harbour, which then blocked the way for the cruisers behind it. This left them unable to help during the following attack.

Run For Your Lives!

Some shells fell on homes, killing or seriously wounding the people inside. Others killed were caught by surprise on the streets. Up to this point none of the local people knew what was happening and thought that the noise was either the battery practicing, or a naval battle out at sea. Many were having their breakfast, and getting ready to start the day. The first civilian fatality was reported to be Hilda Horsley, a 17-year-old tailoress, who was on her way to work.

The people of the two towns were terrified by the noise and destruction, and ran for safety, clutching whatever they could carry. Some gathered in Ward Jackson Park, or made for nearby villages, such as Elwick or Hart.

The damage caused by the attack

The Germans' intention was to cause as much damage as possible to the shipbuilding and engineering works, which were a prime target during wartime. They also hit the gasworks, with the result that no one in either town had any lighting or heating that night or for some time afterwards. By the time the German ships left large areas of the Headland and West Hartlepool had been destroyed. Altogether 127 people were killed as a result of the attack, and another 400 were wounded, some suffering horrific injuries.

The German ships made their escape still hidden by the fog. This was nearly thirty years before the widespread use of radar, so the British Navy was unable to find them. They returned to Germany to heroes’ welcome.

More detail »

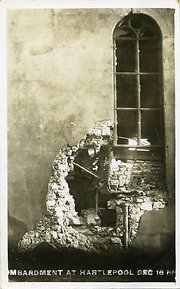

Victoria Place Hartlepool

Victoria Place Hartlepool

Donated by Suggitt Postcard Collection

Donated by Suggitt Postcard CollectionPart of the Hartlepool Library Service collection

Dated 1914

No. 7 Victoria Place Hartlepool was the home of Adjutant William Avery who was Commanding Officer of the Salvation Army in Hartlepool. He was one of the first casualties of the Bombardment on the 16th December, 1914 and is buried in North Cemetery. His death was featured on the front page of the Daily Sketch national newspaper published the day after the Bombardment.

H02423

More detail »