Hartlepool Sports & Leisure

Hartlepool Sports & Leisure

- Cinemas, Theatres & Dance Halls

- Musicians & Bands

- At the Seaside

- Parks & Gardens

- Caravans & Camping

- Sport

Hartlepool Transport

Hartlepool Transport

- Airfields & Aircraft

- Railways

- Buses & Commercial Vehicles

- Cars & Motorbikes

- The Ferry

- Horse drawn vehicles

A Potted History Of Hartlepool

A Potted History Of Hartlepool

- Unidentified images

- Sources of information

- Archaeology & Ancient History

- Local Government

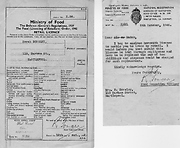

- Printed Notices & Papers

- Aerial Photographs

- Events, Visitors & VIPs

Hartlepool Trade & Industry

Hartlepool Trade & Industry

- Trade Fairs

- Local businesses

- Iron & Steel

- Shops & Shopping

- Fishing industry

- Farming & Rural Landscape

- Pubs, Clubs & Hotels

Hartlepool Health & Education

Hartlepool Health & Education

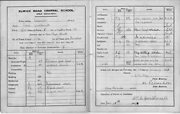

- Schools & Colleges

- Hospitals & Workhouses

- Public Health & Utilities

- Ambulance Service

- Police Services

- Fire Services

Hartlepool People

Hartlepool People

Hartlepool Places

Hartlepool Places

Hartlepool at War

Hartlepool at War

Hartlepool Ships & Shipping

Hartlepool Ships & Shipping

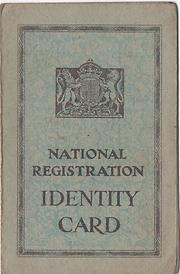

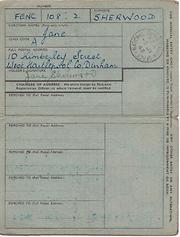

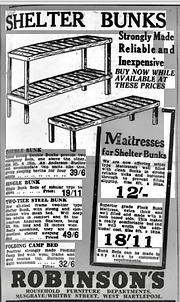

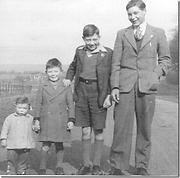

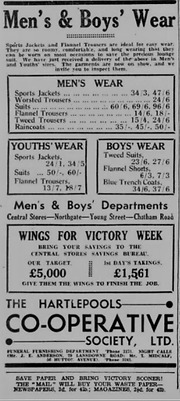

Home Front - Second World War

Details about Home Front - Second World War

A selection of images and documents relating to the 'Home Front', during the Second World War.

Location

Related items () :

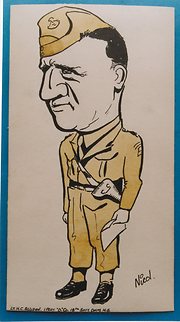

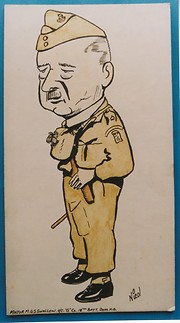

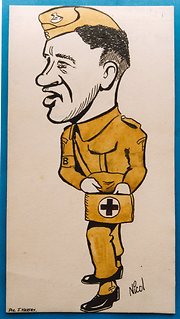

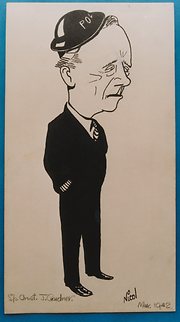

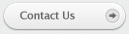

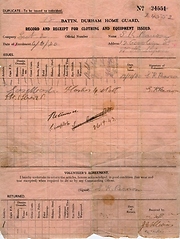

18th Battalion Durham Home Guard

18th Battalion Durham Home Guard

Donated by W Henderson

Donated by W HendersonPart of the Business Cards collection

18th Battalion Durham Home Guard. Flyer for their Grand Finale Smoker in 1944.

More detail » 1943 Wedding of Jack Donkin and Joan Wilson

1943 Wedding of Jack Donkin and Joan Wilson

Donated by Elizabeth Donkin

Donated by Elizabeth DonkinDated 1943

The wartime wedding of Jack Donkin and Joan Wilson at St. Joseph's Church in 1943.

More detail » A Wartime Childhood

A Wartime Childhood

In 2005 Hartlepool's Museum and Library Services worked together on a project called 'Their Past, Your Future', which commemorated the part played by local people in the Second World War. As part of the project Jenny reminisced about growing up in the War years. This is her story, in her own words:

Jenny, born in West Hartlepool in 1929. I was ten year old when the war broke out. I went to Jesmond Road School. I had a brother in the regular army who was in China when the war broke out. We lived in Bellerby Terrace, next door to the police station. I had an older sister who was married and another two brothers at home. Neither of them could go in the war, because of health problems, so they did taxi work during the war. I was at school and had two younger sisters at the Open Air School at the top of Thornhill Gardens. It was like an enormous greenhouse to look at it, it was all of glass. They used to give them treatment with sunray lamps, and special food and milk that healthy children didn’t get. This was for children that had weaknesses. Violet had a weak chest, bronchitis and asthma, and Mary had very brittle bones.

Jesmond Road had air raid shelters in the school-yard, and we went there if the sirens went. If it was really bad we just went to school in the mornings, or just in the afternoons, so we had quite a lot of time off school, but we got a lot of homework to do. But I didn’t have much time to do homework, because my father had horses and wagons, and we had stables at the bottom of our gardens, and I used to help with the horses, clearing the stables out, going to the warehouses for fruit and vegetables to take round on the wagons. And I had a good brain, and was a good speller, and I used to do most of the paperwork and work the food coupons out for him, even though I were only twelve year old at the time. We had two horses at the time, a little white pony and a big brown horse called Paddy. When the sirens went, he used to try to kick the stables down because he was terrified. So I had to go down the stables, even if it was the middle of the night I had to get out of bed and go down the stables and sing to this horse, because that’s the only way we could keep him quiet! He loved “When Irish Eyes Are Smiling”.

I used to get up early in the morning, go down the stables, feed them, clean them out and groom them, ready to go in the wagons. Me dad and me mam had a fruit and vegetable business, like they have a mobile shop now, but with horses and carts. When rationing came in we had coupons for this and coupons for that, and points and all the rest of it. My mother was a trained tailoress and dressmaker, and we used to have a lot of things home made, which was very lucky because she wouldn’t have been able to go to shops and buy them, being so many of us. I remember me sister got a great long length of blackout material, and she bleached it and then she died it yellow, and she made the most fantastic outfit, she made a skirt and a jacket and even a hat to go with it, and it looked really smart because it was yellow and she trimmed it with black.

I had to go down to Foster and Armstrong in Stranton every Monday and Thursday to get the horse feed, ‘cos even the horse feed was rationed. I had to go to the farms; there was one at Greatham and there was one at the top of Cameron Bank which was called Johnson’s, and I used to go there to get the cabbages and sprouts, lettuce and beetroots, sacks of potatoes and things like that to sell on the wagons.

I remember one day, it was on a Monday afternoon and the siren went. I was home from school and I went up in the attics and was looking out the window and I saw a bomb go right up between the row of houses, and it landed the other side of the Sacred Heart school, on a little bungalow that was there. All the windows in the school was blown out, yet the windows in our houses never budged, they didn’t even get a crack in them. Luckily the children weren’t at the school that day. I don’t remember being frightened at all, we just took it in our stride.

We used to get ferocious winters, the snow used to be really deep, and you got no extra fuel because coal was rationed. You just had to make do with what you had. We used to go down the beach and get sacks of seacoal. I remember taking seacoal round selling it for sixpence a bucket to people that couldn’t get down to the beach. You only got one sack of coal a week, I think, and food rationing you only got one egg a week, and I think it was two ounces of tea, two ounces of butter, four ounces of margarine and two ounces of lard, four ounces of bacon and eight ounces of meat for each ration book. I had to go along to the Co-operative Stores at the end of Duke Street, I got two pennarth of bacon bones, a sixpenny shank and any scraps off the cutting machine, and I’d take it home to my grandmother that was staying with us at the time. She used to make a big pan of stew, there was no meat in it, just the bacon bones and loads of vegetables and she always made suet dumplings just to help to fill us up.

The only person that got birthday treats was my sister Mary ‘cos more often than not she was in hospital. She got loads of toys – we weren’t allowed to play with them. At Christmas me mother used to get an empty chocolate box, one with a bonny picture and a nice ribbon on the corner, and she’d get a little sixpenny traycloth, or a pinny, or some little thing to be embroidered, and she’d put some silks and a needle and a thimble, and a tiny little pair of scissors in this fancy box, and that was my Christmas present. And off my aunt I got a sixpenny box of paints and a big colouring book. I always got a silver threepenny bit off me grandmother. At Easter me mother would make paste eggs, hardboiled eggs, and they were always coloured, she used to boil them with onion skins and make them really brown, and then me sister used to paint pictures on them. And my Aunt Doreen, she used to buy us a sixpenny chocolate Easter egg from Woolworths. I never remember a birthday.

I was a proper tomboy with being brought up with five lads. Because what they could do, I could do better. If they’d climbed a tree, I’d climb a tree, but I’d climb higher. If they’d run along a wall, I’d run along a wall, but I’d run faster. I had to be better than them.

During the war there was no toys. I used to go down to Lynn Street at Christmas, and there was a shop called Lithgo’s the pram shop, and they always had dolls in at Christmas. And in the window there was this marvellous baby doll, fully clothed, and I longed for that doll. I never got it, but me mother knew I wanted a doll. One year she got me this great big baby doll, it was a celluloide, and I thought it was wonderful. Me sister had made a set of clothes for it and I was playing with this baby doll on Christmas morning, and I must have been about twelve or thirteen. We were called to have our Christmas dinners, so I left me doll in the parlour on the settee. Me grandmother was with us at the time and she was pretty hefty. And when she’d finished her dinner she went back into the parlour and when I went in me doll was on the floor absolutely flattened – she’d sat on it. Being celluloid it just squashed like an eggshell. I broke my heart over that doll, and I got into trouble for leaving it where she could sit on it! I never had another doll, not a new one. But I managed to scrimp and save pennies and ha’pennies by running messages for people, and I saved up because there was a girl at school said she had a doll and would sell me it for thirty shillings. That was an awful lot of money to a child during the war. You’d run to the ends of the earth for a ha’penny. I’d sweep the back street and I’d swill the yard, I’d do anything to get an extra couple of coppers to get this doll. And it had a paper mache head, arms and legs and it wasn’t very beautiful to look at but I thought it was lovely and I called it Ann. And one day me brother Kenneth threw it on top of the shed roof, where I couldn’t get it. Before anybody could come home it started to rain. Well you can imagine what happened to it, being paper mache. It just went to a mush. It was absolutely ruined.

There was a cookery class at school. One day we’d do laundry work, and the next week we had cookery class. I used to love doing the cooking. We used to have to take a couple of vegetables and we always made a great big pan of stew. And the children that didn’t have very much at home, if they took a ha’penny they could have a bowl of this hot soup. And if you took a penny you got a bun as well as the soup. I used to love it when I could go to school and get a bowl of hot soup. ‘Cos more often than not, on the way to school I’d have a slice of dripping bread, that was the fat off the joint, and we’d have a slice of bread about two inches thick with this pork dripping on in your hand, running to school. By the time breaktime came round I was ready for something to eat.

During the war leather was very short, and they used to make wooded-soled clogs for kids and they were one and eleven pence a pair, and I loved those clogs. But one time I got a real good hiding off the old man ‘cos the kiddy-catcher came round asking why Jenny hadn’t been to school. Jenny hadn’t been to school because her mother had got her a real old-fashioned pair of lace-up boots like in the olden days - someone had given my mother these and they fit me so I had to wear them and I wouldn’t go to school in them, I was so ashamed of them. They never bought me girls shoes ‘cos I was so heavy on them. They used to make me wear me brothers’ boots that they grew out of, and I was ashamed of them as well. I was always getting into trouble for something.

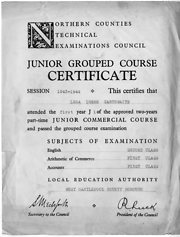

I passed the eleven-plus but me father wouldn’t let me go because you had to buy your own uniform and books and everything and they couldn’t afford it. He said “I didn’t bring you up to be a lady. You were brought into this world to work.” So I started working with the old man when I was twelve, heaving hundred-weights of potatoes around and cleaning stables out and grooming horses. I had to help with the washing and the housework and the baking as well.

Me granny used to bake three times a week. She used a stone and a half of white flour and half a stone of brown flour. We never had bought bread, it was always home-made. But me mother used to buy a twopence-ha’penny loaf, a white one, from the top shop for me dad. And he always had the best butter. Us kids had the margarine and the dripping. Dad got the best butter. But he always had his crusts cut off the bread. We used to fight over who was going to have the crusts because they had a little bit of butter on. But I can honestly say we never went hungry. Me mother always made sure we had a hot meal at least once a day. She used to get stale bread off customers for the horses. She used to get the best clean bits out, and soak it in milk, and squeeze it all out and mix it with a handful of sugar, a good sprinkling of mixed spice and a handful of raisins and it was baked and it tasted lovely. And my grandmother used to make custard, and she made it so thick that when it was cold you could slice it. We’d have a slice of cold custard between two slices of bread and we thought it was a treat! Mother used to mash some boiled parsnip and flavour it with banana flavouring so it was like mashed banana, and we’d have that between bread and margarine, and that was a treat ‘cos you couldn’t get real bananas. And we had chickens down the garden and she used to collect the eggs and put them in isinglass, it was this solution you used to put the eggs in to preserve them, so when the eggs were short, we were never short of eggs. Mr grandmother always made the Christmas cake, and she made them a year previous. She used to wrap them up in cloths and keep them for a full year.

Our house had a scullery, a kitchen, a big dining room and a big parlour. One flight up there was a great big bedroom, and a bathroom and an indoor toilet. Up another flight of stairs there was a small bedroom, the big front bedroom which mother and father was in, and the big back bedroom where us three girls slept. Then up another two flights of stairs was three big attics and the lads slept up there. In the back yard there was an outdoor toilet, a great big coalhouse, a bicycle shed and a little conservatory place. Across the back street was a long garden. We had electricity. Me mother had an electric cooker in the kitchen, and she had electric boiler as well. Oh we were very posh! We ate our meals in the kitchen because as kids we weren’t allowed to sit in the dining room. Oh no, it was too posh! That was only for special occasions like Christmas. At Christmas mother would make us what she called a “mistletoe”. It was hoops of an apple barrel, and she’d put them interlocked. She’d wrap crinkle paper round them and tinsel, and hang these little baubles on it and we’d make things out of paper like rosettes and little flowers and animals and we’d get acorns and fir cones and paint them and tie bits of wool on and put them round this “mistletoe”. And that was hung in the kitchen.

We had an Anderson shelter in the garden, but we never used it. Me mother wouldn’t take us out in the garden in the middle of the winter, we used to stop in our own house. The old man used to say “if you’re gonna die you might as well die in bed”.

Me and our Violet were supposed to have gone on this ship to Canada when they were evacuating the children abroad. At the last minute the old man changed his mind and he wouldn’t let us go. Which I am very pleased about because the ship was sunk. So it was just by good luck.

At Christmas time all the family used to come to our house, it being such a big house. My mother’s people come from Ilkley in Yorkshire and they used to get a charabanc to come through at Christmas time. I remember my grandmother and our Lilly paid into this fund so me, our Mary and our Violet could go to this party in me granny’s street.

I met me husband during the war. It was the end of the war, 1945, and I was fifteen. He was in the navy. I had a cousin who wanted me to go out with her on a Sunday night. I knew she used to go to meet these sailors, ‘cos she was older than me. She said “just come with me ‘cos you’re not allowed on the docks on your own, you have to go in pairs.” She said “just come with me, then when we come back off the dock you can come home.” So I went and I wasn’t allowed make-up or anything like that, ‘cos the old man would have killed us. So her boyfriend saw two of us, and he went and got this friend to come with him. So he said “you can’t go home, I’ve come to take you for a walk.” We went to the shows up at Seaton and we were supposed to get the last bus home and we missed it. So we walked home, and by the time I got home it was eleven o’clock. Me mother was out looking for me. She grabbed me by the hair and she made me run all the way home ‘cos she was on her bike. Luckily enough Bob followed us, he didn’t slink off. And me mother thought he was so charming – he could charm the birds off the trees. So she asked him in and gave him a cup of tea and talked to him. And she told him he could call again. The next time he came later in the week he brought some rum. Of course the sun shone out of him after that. She wouldn’t have a word said against him, and I ended up marrying him. I met him in the August and we got married on January 5th. He was nearly twenty-one and I was sixteen in the February but I got married in the January. I didn’t tell the officials because you weren’t allowed to get married under sixteen. But I wanted to get married because his ship was moving down to Harwich and I wanted to go down to his people, because he wouldn’t be able to get back up here. So my mother let us get married. We had a wedding cake, which most girls didn’t have. It was a Christmas cake, and she put almond paste on it. And me wedding dress was powder blue. My sister had made it. She had got a white blanket off someone she knew and she made me a white hat and coat. And we got married in the Registry Office in 1946.

More detail » A Wartime Childhood by Evelyn Mitchell

A Wartime Childhood by Evelyn Mitchell

In 2005 Hartlepool's Museum and Library Services worked together on a project called 'Their Past, Your Future', which commemorated the part played by local people in the Second World War. As part of the project Evelyn Mitchell from the 'Writing Together' group reminisced about her memories as a child. This is her story, in her own words:

I was six when the war started and had just started infant school at Jesmond Road, our part of the school was requisitioned for soldiers so we were farmed out to anyone that had a spare sitting room and was willing to put up with us. The added bonus of this was that we only went to school half a day. I thought this was excellent.

Eventually we were fitted with our gas masks by the ARP and issued with the square boxes to put our masks in and we spent the next few years with them bumping against our bottoms everywhere we went. My brother, who was three years old at that time, was as wide as he was tall and resembled a squat Michelin man, was too young for a junior mask and was issued with a baby gas mask. This looked like a large black rubber egg with a plastic visor and my brother, protesting vigorously, was crammed inside this thing, the trouble was his fat little legs hung outside and he looked just like Humpty Dumpty. There was nothing in between the egg and a junior mask so he was destined to spend the first two years of the war without any protection. My mother was in constant terror that her youngest offspring would be offed in a gas attack. I PRAYED FOR ONE CONSTANTLY.

The war was a year old when it was announced that all children aged five years and over were to be evacuated to Whitby and my cousin Mary and I were to go together. I was in seventh heaven as my maternal grandparents came from Whitby and it had always seemed to me that everybody in the family had been there but me. Off we went, my gas mask bumping against my body in my haste as I scurried along, worrying all the while that she would change her mind (I didn’t trust my mother). We got to the cemetery gates, in sight of where everybody was to meet when she stopped, “You’re not going – if we are going to go we will all go together”, she said. I was dragged off protesting but to no avail. Looking back I have often wondered how I would have coped as the bond with my mother was very strong. My cousin Mary stuck it for two years before absconding, she was picked up in Middlesbrough bus station as she waited for the Hartlepool bus. She was nine years old at the time (mind, she was a masterpiece – everybody said so).

When I moved to junior school we had regular tests on what to do during an air raid/gas attack, by then we had brick shelters built in the school yard with wooden benches built in them. Every few weeks the Fire Brigade would turn up to fill these sheds with black smoke (in lieu of gas) and we would stumble around in complete darkness, wearing our gas masks. If we had dirty faces when we came out our gas masks were leaking. As you can imagine, these tests were not popular with us as we came out with cuts and bruises and the occasional black eye. Mercifully, we were never to use our gas masks or the school air raid shelters and there was great relief all round when they were eventually demolished.

The air raid warden in our street was a Mr Garrington who was over the moon at being appointed warden. He was a nice man who took his ARP duties very seriously; he was on the point of retirement when the war started so it gave him a new lease of life. Unfortunately he became quite pompous and strutted up and down the street telling everybody what to do; he became a bit of a pain in the neck. My father wasn’t the kind of man to suffer fools gladly and regarded our air raid warden as an “old fart” and didn’t hesitate to let him know this. Mr Garrington paid him back by knocking on our door every other night accusing my father of “showing light”. This infuriated my father because the whole street knew it wasn’t true but he still had to go out and check.

My father was in the Home Guard after he was discharged from the army on health grounds; he was considered a prize because he had done his “square bashing” and had been trained to fire a rifle and small arms – but most importantly he had been allowed to keep his rifle (it was before Dunkirk) and his uniform, as it was known he would be going into the Home Guard. My father did a full days work in the shipyard and then reported for guard duty most nights, leaving home about 7 o’clock in the evening and returning about 5 o’clock the following morning face grey with fatigue. Sometimes he was wet to the skin, but he never said where he had been or what he had been doing. He had a couple of hours sleep and went to work. His life was no different to any man still at home, everyone did something. On top of these extra duties everybody had to do fire watching, usually at their place of work or at public buildings. This involved looking out for incendiary bombs which were dropped for the sole purpose of setting fire to buildings.

My mother was one of the street deputy wardens and her best friend was the other, mother manned the hose pipe and her friend was in charge of the stirrup pump. Mother was 4ft 11ins tall and six stone ringing wet and her friend was 5ft 9ins and looked like Olive Oyl. When the ARP turned up to test their fire fighting skills the whole neighbourhood attended to watch as it was better than going to the pictures. The sight of my pint sized mother lying prone in the road trying to hit a bucket with a hose where the water came out in fits and starts, remains with me to this day; her friend, whose job it was to supply the water hadn’t the strength in her legs to raise the water pressure no matter how frantically she pumped away. I don’t think they ever hit that bucket.

Two of my uncles were in the AFSI; as they were in reserved occupations they were not eligible for call up. They both worked for a local builder and were experts in demolishing houses and so, at night they fought fires caused by the bombing and during the day they made the damaged houses safe. It was dangerous and dirty work, especially if they had only a couple of hours sleep the night before but it had to be done as long as the bombs kept falling.

The blackout was a real problem because it was literally what it was – pitch black; if there was no moon you did not know where you where, not that you wanted a moon as it lit up the place like a Christmas tree and the blackout didn’t matter, we were sitting ducks. My mother was in dire need of a new coat before the war started but because of clothes rationing it took two years before she managed to save enough clothing coupons to buy one. She used to borrow books from a library a local newsagent ran as a sideline, it was only a few hundred yards away in a straight line. Unfortunately she couldn’t resist wearing her new coat and, as several streets ran off the road she was using, she veered right in the pitch darkness and walked into a wall. She stumbled home with a broken nose, her new coat held to her face to stem the blood. The coat never recovered. I smashed my front tooth in a similar fashion, only I walked into a lamp post.

More detail »

A child's view of the War by Ray Cummings

A child's view of the War by Ray Cummings

In 2005 Hartlepool's Museum and Library Services worked together on a project called 'Their Past, Your Future', which commemorated the part played by local people in the Second World War. As part of the project Ray Cummings reminisced about being a child in the War years. This is his story, in his own words:

I was born 1934 and started school in 1939, the year war broke out. I can remember we all gathered in school and the teacher told us what was happening and we were only five year old. Later on about 1940 or ‘41 I went to school with me cousin who was the same age as me. The teacher took her out and told her her father got killed on the beach. He was going down Marine Drive to the beach for sea coal and he’d seen this old chap trying to put a mine in a pram, and he went to stop him and it blew up and they both got killed. Later on they barricaded the beach off, put barbed wire up. There were soldiers there at the Spion Kop area and also on the Town Moor, and we used to go down, my friends and me, and they used to give us sandwiches, bread and jam and things like that. Food was the shortest thing, then. I lived in Mary Street on the Headland, and it was about three streets away from Marine Drive and the seafront. And there was the Steetley Magnesia factory up on the Spion Kop, and the Germans used to come over and try and bomb it. The German bombers used to follow the rivers up to the steelworks around Middlesbrough and come back, and any bombs left got dropped at Steetley or Hartlepool. They dropped this land mine and it hit Marine Drive and all the windows for about three streets were put out. And I can remember another family on the Central Estate where a bomb dropped on a house and the family were killed.

Me father worked in the Steetley Magnesia and my elder brother worked in the shipyard and that was a job were you couldn’t go in the Army. Father and me brother were in the Home Guard and used to bring their guns home, no bullets in but we thought that was a great thing. They had the Army uniform and they had a rifle.

I went to St Bega’s School and they built an air raid shelter there. It was for not only the schools but also people living round that area. And some people had their own shelters in the back garden. Anderson shelters which they got off the government. Me granny lived a street away and she used to come down every night to sleep at our house because she was by herself. She was frightened and we used to take her down the shelter. They took blankets down there. Took maybe food because you might have been there all night. And people used to just sit. There was seats and it was a bit dampish naturally, but we had sing-songs to cheer us up. Then you could hear the siren going and the warden would come down and say “right ho, it’s all clear, back home”. And you got used to it in the end. I knew nothing else but that when I was a boy – War. It was a good time in a way, but a bad time for people. If you seen a telegraph boy going to a house you knew somebody had gone.

You used to hear the German planes coming and you knew they were Germans because there was a sort of different zoom in the engines. And if you went out and looked up you could see the searchlights and then the ack-ack firing at them. I can remember on the docks at Hartlepool they used to have barrage balloons. It was big, full of gas and they used to hang them over the dock areas and if the Germans come low and hit that they used to get entangled in the thing. It was chained, fastened down to the ground. I can remember once when one of the balloons escaped and they had to chase it, and they caught it and brought it back. The balloons were a deterrent in a way, to keep the Germans away from the docks. But they still come over and bombed. They were after Steetley Magnesia because they knew Steetley used to get stuff out of the sea that was going in to make steel. Something in the magnesia they’d got out of the sea was into the making of steel. I don’t think they ever bombed it, but they hit Hartlepool a few times.

I would be about six or seven years old and I didn’t know nothing about what was going on, but me mother and father used to tell us about things and Hitler and all that. We used to listen to the radio a lot to Lord Haw-Haw and all that. You were a bit frightened at the time, you know, because England had nothing to defend ourselves. But it was a great time for the community because we used to get together and help each other. Neighbours helped you. You had a ration book and you only got so much sugar and so much meat and that. But the mothers were great because they used to make a stew called Panakity, with all sorts tossed in, and they baked their own bread. You weren’t hungry, there was always something there when you got home from school. Your mother had done something, or maybe a lady next door had made a pan of stew and there was some left and she gave it to you. Or my mother maybe baked and gave her some stuff. They really got together- communities.

It was a very exciting time for a boy my age. We used to go to the pictures and maybes a cowboy was on, Roy Rogers or something, and then all of a sudden you had to go out because there was the air raid sirens. You had to go down the shelter and listen, wait and then go home. And there was no lights, it was all dark. Mothers and fathers knew if you get caught in an air raid that somebody else will take you down the shelter and help you. You still played your school football and stuff, and it was a great time like that. The footballs had a bladder inside, not like these of the present day. So if you hadn’t a football you had a bladder, and kicked that about. You played cricket with a bit of wood and a few sticks. Or you played “kick the tin”. Another game was bouler. It was a cycle wheel - the steel, what the tyre goes on. Take all the spokes out, you had a ring. And get a bit of wire on a stick and you used to put the wire round it and run around, and it was great. We used to race each other, try to do tricks with it. There was no youth clubs or nothing like that. We used to go all round the town. Your mother would let you out because they knew you were safe, not like there is today. I remember we were going on this trip to West Hartlepool. That was a few miles away. We thought it was great going on the bus, and we won playing another Catholic school, I think it was St. Joseph’s, at football. We were only going a few mile away, and that was great because you never left your little place where you lived. It was like a little village on the Headland and everybody knew you.

At Christmas you used to make streamers for decorations because you couldn’t buy them. You didn’t get a lot of presents. I remember my father knew this chap who used to make these wooden tanks, and we used to get them. Maybes sometimes you got an orange, but you never got no bananas, they were rare. I can’t remember seeing one till after the war. Didn’t know what they were. You used to go round to the butchers and take your ration book. You had the clothing coupons and all, to buy clothes. Or people passed them down. A neighbour had an older son than me, and she passed the clothes down – his clothes to me. In summer a lot of the children played in their bare feet. Now and again you used to get a new pair of boots for the winter. But there again kids grow out of boots and you pass them down to your younger brother. And me father had a last to cobble his own shoes. He got the old rubber off the conveying belts at Steetley Magnesia and put it on our boots. Because you couldn’t get leather, so you put that on your boots. It made you about another six feet taller, but it lasted. And he used to cut our hair. He had these shears and we used to get what they called a “tar brush”. It used to be all cut short with a little tuff on the front. But everybody was like that. There was nobody who would take the Mickey out of you because everybody was the same.

I can remember on VE-Day we listened to the radio and I remember Winston Churchill making his great speeches. And this man with a big drum and all the people with young kids behind him singing and shouting and going round the town, on the Headland, banging this great big drum because the war was over. They had street parties and all the kids were invited. And again the mothers found food, they made cakes and puddings and things like that. Jelly and custard and stuff. We were stuffing ourselves with food which we had never seen. I can remember after the war when men were coming home from Japanese and German prisoner of war camps and they were putting street parties on for them. But the Japanese prisoners of war couldn’t eat a lot of food because they were starved, because their bodies had shrunk.

It’s a great time when the community’s together, and that’s what it should be today. They were very close then.

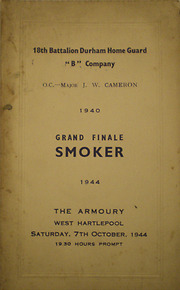

More detail » ARP Anti-gas Training

ARP Anti-gas Training

Donated by Mrs. Jean Sutherland

Donated by Mrs. Jean SutherlandDated 1943

Henry Robertson's Certificate awarded on his completion of an Anti-gas traing Course in September 1943.

More detail » ARP Instructors

ARP Instructors

Donated by Hartlepool Museum Service

Donated by Hartlepool Museum ServiceARP Instructors, assisted by Police Officers, teaching revival techniques.

More detail » ARP Wardens

ARP Wardens

Donated by Hartlepool Museum Service

Donated by Hartlepool Museum ServiceGroup of ARP wardens next to Binns van.

More detail » ARP Wardens

ARP Wardens

Donated by Hartlepool Museum Service

Donated by Hartlepool Museum ServiceGroup of wardens beside salvation army van.

More detail » ARP Wardens

ARP Wardens

Donated by Hartlepool Museum Service

Donated by Hartlepool Museum ServiceFive men, three in uniform. two with numbers on their chests.

More detail » ARP women

ARP women

Donated by Hartlepool Museum Service

Donated by Hartlepool Museum ServiceWomen & bicycles at Report centre. Women are wearing military helmets.

More detail » Ada Proctor's (nee Tennick) War Memories

Ada Proctor's (nee Tennick) War Memories

I was born in Sunderland as a twin and at 17 went to Shildon to work in the Auxilliary Fire Service to man telephones and fire watching at the Bishop's Palace in Bishop Auckland on a Sunday.

At 18 I went to Leeds and worked in an aircraft factory making parts and for 12 hour shifts stood at machines milling and drilling but had to leave on medical grounds because of the noise.

I then joined the Land Army, went to Durham to collect my uniform and was sent to Wolviston. I had to put the harness on the horse, yolk up and deliver milk churns. After that, I went to a market garden at Egglescliffe and worked with German prisoners. Being in the Land Army was very hard and not as it is portrayed in films and that makes me mad ! We never let on to farmers that we hadn't done something before or it would be even harder! My wrists were always red and swollen and I remember endless tatie picking, potato snagging and one bad job was picking sprouts with ice on.

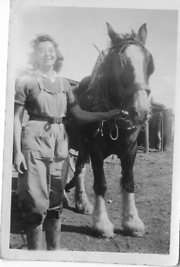

Our uniforms were very dull and my twin sister Olive and I (she worked on a farm at Elwick and her picture can be seen with a horse) would go to a stall on Stockton market and buy dusters to make knickers and any bits of ribbon we could find and we used to embroider them to make things look a bit more fancy.

We were allowed one jar of jam a month and had to sign for it.

Eventually I ended up on a farm at Hart and married the local blacksmith.

More detail » Ada Proctor: Digging for Victory

Ada Proctor: Digging for Victory

In 2005 Hartlepool's Museum and Library Services worked together on a project called 'Their Past, Your Future', which commemorated the part played by local people in the Second World War. As part of the project Ada Proctor from the 'Writing Together' group reminisced about the Women's Land Army. This is her story, as told to Chris Eames and Margaret Sanderson

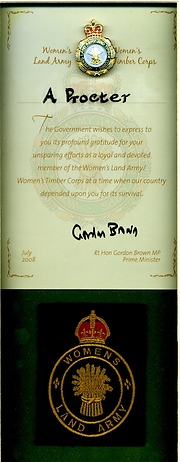

During World War Two, several cries went out to the nation: ‘Dig for Victory’ and ‘Your Country needs YOU!’ were just two of those cries. Owing to a shortage of able-bodied men (they were mostly in the armed forces), the Women’s Land Army was set up, enlisting young women to work on the country’s farms, in an effort to boost the economy and food supplies for this country.

A local young lady – Ada Proctor, (nee Tennicke) – was one among many, including her twin sister, who answered the challenge. Ada, age eighteen, was already working for the war effort, in a munitions factory in Leeds, but, filled with patriotic zeal and youthful energy, she was quick to exchange a factory bench for what must have seemed a more exciting way of life, as the Women’s Land Army promised plenty of fresh country air, plus many new experiences.

The uniform was attractive; fawn cavalry-twill breeches worn with smart polished brown boots, bottle green jerseys over crisp white shirts, finished off with the regulation tie. A fawn overcoat and broad-brimmed hat completed the ensemble.

Ada was offered no training ‘plunged in at the deep end’, she laughingly recalls, remembering the first farm she was sent to. Threshing, which meant working on top of the stack and forking down barley, oats or wheat, was one of her first tasks. A heavy job for a slip of a girl; no mechanical help in those days! Fortunately, an older girl who knew the ‘ropes’ took Ada under her wing and was a great help to her. Only when she was back at the hostel in Wolviston (where all the girls stayed), could she soothe her aching muscles.

Dairy farming and work with animals was next, work that gave Ada a lifelong love of animals and the countryside, which eventually led to her marriage with Bill the local blacksmith.

Working with cows, learning to milk, cleaning out and handling milk churns, which held five gallons of milk, each. She learnt to harness the pony in the trap – a Rolley – and deliver the milk from door to door, using a special ladle to measure out the milk.

Ada can never recall being allowed to have her meals with any of the families she worked for. Her lunches were packed up by Polly, the cook at the hostel, and were chiefly beetroot and cheese sandwiches, washed down with tea from her flask. Sweets and any sort of dessert were in short supply because of rationing; one jar of jam per month was the allowance!

Work on the farm began at 8 o’clock, and most of it was back-breaking especially during the potato picking season, as it was all done by hand, the same as gathering leeks and sprouts. Ada mostly enjoyed the contact with livestock – though one cow, she recalls with horror, had its own livestock, running all over its body – mites! Nevertheless, she took to milking and dairy work as if born to it. What she didn’t enjoy was the occasional slap round the face from a dirty, wet, cows tail! That, she says, is where the notion of the job being romantic ended!

One memorable Christmas Day, she spent in the cow-byre, washing and grooming the herd, and the winter of 1947, when snow fell all over the country to a depth of 4 feet, making roads, lanes and fields impossible to reach, Ada and friends had, somehow, to feed and water stranded animals.

Land Army girls were not the only ‘helpers’ on farms during those years. Prisoners of war appeared on many farms where Ada worked. Asked if she ever felt threatened by their presence – they were after all, our enemies – she replied that she never had, and furthermore, found the men polite and courteous, despite the language difficulty.

As the war continued, so did Ada’s education on the land. She learned to drive a tractor, herd sheep, harness horses – and discovered the cure for a sprained wrist! (Her own sprained wrist)! An old farmer urged her to try his favourite remedy for sprains – maiden’s water and barley!

All the farms were without electricity. Oil lamps, flat irons and earth closets were the order of the day. Despite the hardships of rural life, there was great camaraderie among the Army girls, who usually met up for some social life, dancing and meeting young men, at the Sappers Camp at Greatham. Great friendships which last to this day, were forged during those times, and the ‘girls’ still meet up at their annual reunions. Sadly, the Women’s Land Army and stalwarts like Ada Proctor, have until recently, gone unrecognised.

Only in recent years, have these proud and courageous women taken their rightful place at Remembrance Services and such.

Those gallant girls worked their hearts out, playing their part and digging for the victory that this country of ours accomplished, and we salute them all.

More detail »

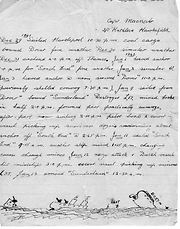

Air Raid Diaries 1940 by Joan Dalkin

Air Raid Diaries 1940 by Joan Dalkin

Joan Dalkin was born in 1921. At the time of keeping this diary she was working as a secretary at the shipbuilding firm of William Gray & Co. Ltd. During the war she lived with her parents at 4 Brougham Street, Hartlepool.

Air raid warnings at Hartlepool during 1940

|

January 29th |

Air raid warning 9.30 to 10.30 |

|

February 16th |

Cossack rescue 300 men from prison ship Altmark in Norwegian waters. |

|

March 13th |

Peace between Russia and Finland |

|

May 9th |

Germany invade Holland and Belgium |

|

May 23rd |

Germans capture Bologne |

|

June 6th |

605 000 men arrived in England from Dunkirk |

|

June 7th |

Air raid warning 1:10am to 1:50am |

|

June 8th |

Air raid warning 1:58am to 2:07am |

|

June 10th |

Italy declared war on Allies |

|

June 13th |

6 000 English men captured by Germans in France |

|

June 14th |

Germans enter Paris |

|

June 17th |

French have asked Germans for peace terms |

|

June 18th |

French are still fighting |

|

June 19th |

Air raid 11:15 until 4. Went to bed 3:15. Bombs dropped on Musgrave Street. Two people killed, several injured. |

|

June 21st |

Air raid warning 1:10am to 1:50am. |

|

June 22nd |

French ship sunk off Tees, 150 workmen onboard, only eight saved. |

|

June 23rd |

French accepted terms from Hitler. Armistice signed 16:50pm (Saturday). Terms not known by French people. |

|

June 24th |

Air raids on London, SE coast and Midlands. Three people killed. French colonies are to fight on. |

|

June 25th |

Air raid 11:55pm to 2:30am. No bombs on Hartlepool. |

|

June 26th |

Air raid 12:05am until 1:50am. No bombs on Hartlepool. |

|

June 27th |

No siren sounded but in shelter from 12:45am until 2:30am. Bombs dropped on Middlesbro. |

|

June 30th |

Air raid from 12:15am until 1:35am. No bombs on Hartlepool. |

|

July 1st |

Air raid on Scotland about 8pm. |

|

July 2nd |

Air raid at Newcastle 5:30pm. Many injured, ten dead. Plane brought down off Hartlepool. |

|

July 3rd |

One plane brought down off ?? early this morning. |

|

July 4th |

French navy attacked by British, many vessels taken others destroyed. |

|

July 5th |

Remainder of French navy ordered by Petain to attack British Fleet. Air raid 12:15am until 2:50am. Gunfire heard. |

|

July 6th |

Air raid 10:30pm until 11:20pm. Gunfire heard 1am until 2:30am. Bombs dropped off Fairy Cove battery into sea. |

|

July 7th |

10:45 until 10:47 gunfire after all-clear12:20am until 12:45am. |

|

July 10th |

Air raid 11:35pm until 12:40am air raid 5:45am until 6:15am. Gunfire first time. |

|

July 11th |

Air raid 2:45am until 2:30am. No bombs dropped on Hartlepool. |

|

July 12th |

Air raid 11:50pm until 1:35am. Gunfire. Air raid 3:20am until3:30am. Nothing happened. |

|

July 13th |

Air raids 6:25pm until 6:40pm; 2:55am until 3:35am; 3:40am until 4:10am. Nothing happened. |

|

July 15th |

Air raid 11:15pm until 2:20am. Gunfire. |

|

July 16th |

Air raid 11:37pm until 1:35am. Gunfire. |

|

July 18th |

Air raid 11:57pm until 1:35am. Gunfire in distance. |

|

July 19th |

Air raid 11:55pm until 12:40am. Nothing happened. Gunfire about 3am, no warning. |

|

July 20th |

Air raid 12:50am until 2:20am. Bombs dropped on Tin Box Factory. Nobody killed. |

|

July 21st |

Air raid 11:58pm until 2:20am. Gunfire. Estonia, Latvia, Lithuania joined Soviet Union. |

|

July 22nd |

Air raid 11:46pm until 12:26am. Gunfire in distance. |

|

July 23rd |

Air raid 3:40am until 3:50am (action before raid warning). |

|

July 26th |

Air raid 11:50pm until 1:45am. Gunfire. |

|

July 29th |

Japan has arrested British subjects. |

|

July 30th |

Mr Churchill visited Seaton Carew. Did not see him. |

|

August 1st |

Air raid 12:15am until 1:45am. Gunfire. Leaflets dropped in south-west etc. |

|

August 2nd |

Air aid 12:10am until 1:30am. |

|

August 3rd |

Air raid 12:10am until 1am. |

|

August 5th |

Air raid 10:40pm until 1:20am. Gunfire. |

|

August 7th |

Air raid 11:05pm until 12:20am. |

|

August 8th |

Air raid 11:10pm until 12:20am. |

|

August 9th |

Air raid 2:20am until 2:50am. |

|

August 11th |

Air raid 11:55pm until 2:25am. |

|

August 12th |

Air raid 10:50pm until 1:30am. Gunfire. Sixty-two planes shot down. Thirteen Allied down, two pilots safe. |

|

August 13th |

Seventy-eight planes shot down off south coast. Thirteen of Allied planes missing. Ten pilots safe. |

|

August 14th |

Air raid 11:10pm until 1:30am. |

|

August 15th |

Air raid 1:03pm until 2:15pm. Very heavy gunfire. One plane brought down. One British landed on golf course. Air raid 11:10pm until 11:35pm; air raid 11:55pm until 12:35am. Pilot of plane still alive. 180 planes brought down. |

|

August 19th |

Air raid 10:15pm until 10:50pm; 11:30pm until 12:30am; 1:40am until 2:20am. Gunfire. |

|

August 22nd |

Air raid 12:40am until 1:40am. |

|

August 23rd |

Air raid 2:20am until 2:38am. |

|

August 24th |

Air raid 12:35am until 5:05am. Gunfire, bombs at West Hartlepool SW. |

|

August 25th |

Air raid 10:22pm until 11:10pm; 12:10am until 3:15am. Gunfire, bombs at West Hartlepool. |

|

August 26th |

Air raid 10:25pm until 3:45am, heaviest gun fire yet. Bombs dropped in Church Street “Edgar Phillips”, three killed. |

|

August 27th |

Air raid 11:30pm until 1:30am; 2:30am until 3:30am. No gunfire. Bombs in distance. |

|

August 26th |

Air raid 10:10pm until 10:48pm. |

|

August 29th |

Air raid 10:50pm until 12:20am; 1:20am until 5:05am. Gunfire, bombs dropped Hilda Street, Mainsforth Terrace. |

|

August 30th |

Air raid 8:50pm until 9pm; 11:45pm until 12:15am. Nothing happened. |

|

August 31st |

Air raid 12:25am until 3:25am. |

|

September 1st |

Air raid 12:25am until 3:25am. |

|

September 2nd |

Air raid 10:10pm until 12:20am; 1:10am until 2:25am. Gunfire etc. |

|

September 3rd |

Air raid 10:10pm until 11:57pm; 12:25am until 12:40am; 12:55am until 1:40am. Gunfire etc. |

|

September 4th |

Air raid 10:55pm until 11:40pm; 1am until 4:22am. |

|

September 5th |

Air raid 10:25pm until 2:25am. Gunfire in distance. |

|

September 6th |

King Carol of Rumania abdicated in favour of his son. Air raid 10:25pm until 2:25am. |

|

September 7th |

Air raid 1:15pm until 1:25pm; 12:15am until 12:20am; 1:15am until 2am. |

|

September 8th |

Air raid 2:15am until 3:35am |

|

September 9th |

Air raid 9:15pm until 9:20pm; 2:15am until 3:50am. |

|

September 10th |

Air raid 2am until 3am. |

|

September 12th |

Air raids 11:55pm until 1:20am; 4am until 4:30am. |

|

September 14th |

Air raid 10:30am until 10:50am. |

|

September 15th |

Air raid 3:05am until 4:10am. |

|

September 16th |

Air raid 2:40pm until 2:55pm; 3:55pm until 4:20pm; 6:45pm until 7:10pm; 7:45pm until 8:50pm; 9:30pm until 9:45pm; 2:15am until ? |

|

September 18th |

Air raid 3pm until 3:20pm; 8:50pm until 9:45pm. Gunfire. |

|

September 19th |

5pm until 5:40pm; 1:05pm until 10pm; 12:15am until1245am. |

|

September 21st |

Air raid 7:10am until 7:15am; 8:30pm until 8:50pm; 9:35pm until 12pm; 1:25am until 1:50am. |

|

September 22nd |

Air raid 3:45am until 3:55am. |

|

September 23rd |

Air raid 4am until 6am. Gunfire etc. |

|

September 24th |

3:55am until 5:55am. |

|

September 26th |

11:05am until 11:30am. |

|

September 28th |

Air raid 3:35am until 4:25am. |

|

September 29th |

Air raid 5:15pm until 5:35pm; 3:45am until 4:15am. |

|

September 30th |

Air raid 12:30am until 1:25am. |

|

October 1st |

Air raid 12:15am until 12:30am; 1:15am until 1:33am. |

|

October 2nd |

Air raid 12:30am until 12:55am; 1:15am until 1:33am. |

|

October 5th |

11:50pm until 1am. |

|

October 7th |

Air raid 8:15pm until 9:45pm; 9:55pm until 10:25pm. |

|

October 8th |

Air raid 11:35pm until 11:45pm. |

|

October 9th |

Air raid 8:45pm until 10:35pm. Gunfire etc. |

|

October 10th |

8:15pm until 10:15pm; 10:35pm until 11pm; 4am until 4:35am. |

|

October 11th |

Air raid 8:30pm until 10:30pm; 11:45pm until 1:45am. |

|

October 12th |

Air raid 8:07pm until 8:45pm. Examination ship bombed, sinking in dock. |

|

October 13th |

7:35pm until 8:45pm. |

|

October 14th |

2:35am until 2:50am. |

|

October 16th |

Air raid 8pm until 8:20pm; 2:35am until 2:50am. |

|

October 19th |

Air raid 8:20pm until 8:55pm; 9:40pm until 10:35pm; 11:35pm until 11:50pm; 1:15am until 1:45am. Slept through the last one. |

|

October 20th |

Air raid 7:50pm until 9:10pm; 3:10am until 4am. MEMORANDA: 126 raids. |

|

October 21st |

Air raid 8:25pm until 9pm; 11:50pm until 1:10am. Slept through last one. |

|

October 23rd |

7:25pm until 7:35pm; 11:10pm until 11:35pm; 3:20am until? |

|

October 24th |

Air raid 9:30pm until 9:45pm; 11:30pm until 2:20am. |

|

October 25th |

Air raid 12:20am until 1:40am. |

|

October 26th |

Air raid 7:35pm until 8pm; 12am until 1am; 1:15am until 1:40am; 2am until 2:30am. |

|

October 27th |

Air raid 5:45pm until 7:10pm; 8pm until 8:20pm; 9:45pm until 10:50pm; 12:25pm until 2:30am. |

|

October 28th |

Air raid 8:45pm until 12:15pm; 3am until 4:30am. Italy invaded Greece. |

|

October 29th |

5:50pm until 7:10pm; 8:30pm until 8:50pm; 9:25pm until 11:15pm; 12pm until 2:15am; 3:15am until 4am. |

|

October 30th |

1:35pm until 2:30pm; 8:30pm until 8:55pm. |

|

November 1st |

6:45am until 7:15am; 1:37pm until 1:57pm; 5:30pm until 6:40pm; 10:30pm until 11pm. |

|

November 2nd |

British troops landed at Crete. |

|

November 3rd |

5:45pm until 6:40pm. Breerge Annie mined off Hartlepool. |

|

November 4th |

Air raid 3:15pm until 4:05pm. |

|

November 5th |

5pm until 5:20pm; 5:45pm until 6:05pm; 11pm until 11:30pm. Roosevelt re-elected. |

|

November 8th |

Air raid 8:20pm until 10:25pm; |

|

November 9th |

Air raid 7:45am until 9am; 6:40pm until 7pm. Mr Neville Chamberlain died. |

|

November 12th |

Jervis Bay saved 35 ships in convoy (three not saved) when attacked by P. Battleship. |

|

November 13th |

Air raid 11:05pm until 12:10am. |

|

November 17th |

1am until 8am. |

|

November 18th |

Air raid 8:10pm until 10:40pm. |

|

November 20th |

Hungary joined Axis. |

|

November 21st |

Air raid 3:40pm until 3:50pm. |

|

November 23rd |

Air raid 6:20pm until 7:10pm. |

|

December 11th |

Greeks captured over 20 000 Italians. |

|

December 12th |

Gunfire no siren. Lord Lathian, British Ambassador to America died suddenly. |

|

December 13th |

Air raid 8:20pm until 9:10pm. |

Air Raid Patrol by Margaret Brain

Air Raid Patrol by Margaret Brain

In 2005 Hartlepool's Museum and Library Services worked together on a project called 'Their Past, Your Future', which commemorated the part played by local people in the Second World War. As part of the project Margaret Brain from the 'Writing Together' group reminisced about her experiences of Air Raids. This is her story, in her own words:

When I was fifteen I left school and became a clerk at a fruit merchants in Whitby Street. This was soon after a bomb had destroyed St James’ church and a school in Musgrave Street. As a result, the windows in our office were partly boarded up which made the office quite dark.

My uncle was a leader in a demolition squad involved in rescuing people who were trapped in the ruins of bombed buildings. One night we had an air raid and the first land mine ever was dropped in Elwick Road damaging a large number of properties and killing about eleven people.

Most houses had an Anderson shelter in the back garden but we had a Morrison shelter. The shelter consisted of a large sheet of cast iron surrounded by cage wire. It was more than double bed size and was always made up for a bed. My mother used the top of the shelter as a table for cutting out clothes patterns.

I remember going to the Forum cinema one night when there was an air raid warning. My friend and I decided to stay and watch the film, but eventually, the sound of bombs being falling drove us out into the street to seek shelter. Outside, the sky was alight with flares being dropped by the enemy aircraft so that they could see their targets. The planes were trying to hit the steelworks and shipyards.

At the age of eighteen many women were conscripted to work in factories or munitions. I wanted to join the Women’s Royal Naval Service but by the time I was of age to enrol, the government of the day decided not to take on any more recruits and so closed entry. However, my boss decided that I should apply for deferment since we were so short staffed.

My immediate boss was an Air Raid Precaution Warden in his village of Greatham. He was also in the Home Guard and did fire watching at night. All this work made him ill and as a result my work load increased. I was then deferred right up to the end of the war. During this time I began work at the report centre which was based underground at the Gray Art Gallery. I did shifts every fourth day after my normal day at the office. During an air raid we had to man the phones and report casualties and damage. We slept in the Art Gallery when it was quiet. We had screened beds and bedding and downstairs we could play table tennis or snooker. The young messenger boys had sleeping quarters downstairs, their job was to take messages on bicycles throughout the town to those caught up in the aftermath of war. We were paid a little money and it helped to supplement our small amount of wages.

At the end of the War, I became a blood donor which was a comparatively new thing at the time.

More detail » Air Raid Precaution Instructors (ARP)

Air Raid Precaution Instructors (ARP)

Donated by Hartlepool Museum Service

Donated by Hartlepool Museum ServiceTaken in front of mobile canteen before going off to see some bomb damage.

Some of the people in the picture look like dignitaries which is borne out by the presence of a senior police officer.

Picture possibly taken in Museum Road with the ABC cinema on the right and the old Police Station in the background.

More detail »

Air Raids and Babies by Edith Lund

Air Raids and Babies by Edith Lund

In 2005 Hartlepool's Museum and Library Services worked together on a project called 'Their Past, Your Future', which commemorated the part played by local people in the Second World War. As part of the project Edith Lund reminisced about her life as a young mother in the War years. This is her story, in her own words:

I was married in 1938. I was living in Streatham Street and my husband was in the Artillery and I used to write him all these letters. Well I wrote him a letter and I wanted to post it to him. I took the little one, he was about a year and three months old, I took him with me to the Post Office which was in Whitby Street, which was quite a walk, because I wanted a stamp to put on it. So I put a stamp on and posted it in the box and I was coming back, and I just got into Musgrave Street and the siren went. Well, he couldn’t walk very far cos he was only a baby, so I picked him up and tried to run a bit, but I couldn’t. I put him down again and the warden in Musgrave Street said “get off the streets, didn’t you hear the siren go?” I said “yes, I heard it, but I can’t get home any quicker.” I was pregnant at the time, it was just before I had the baby, I think, and of course I couldn’t run very quick. I got round into Rokeby Street, just past the school, and all of a sudden me brother, he’d come home on leave from the Air Force, and he come racing down and he grabbed the baby and grabbed hold of me hand and he raced back with me, back to the house, got into the house, under the stairs. All of a sudden they dropped the bombs. And the poor warden I’d been speaking to, he was killed. I felt so sorry for him. Cos he was worried about me and he was killed hiself. Our roof was hit, and we were sitting underneath the stairs. It never come through the stairs, so we were lucky. Everything was shattered all over the stairs, parts of the roof; you could look straight up and see the sky. And the floor was about six to ten inches in soot, because everybody then had coal fires, so the chimney pots was down. The curtains and the window frame was out in the street. So how lucky, because people got worse than that because all those in Musgrave Street, the shops got knocked down, there was the fish shop called Moons, then there was a doctors and the cobblers, the Fruit Market, all knocked down, nothing left. I felt sorry for them, I did. Anyhow, we stopped under the stairs until the all-clear went, and we come out, we just couldn’t believe it.

Anyway, we got over it, and got the house all cleaned up and everything. Took some doing; I could smell soot for weeks after. I lived in the house on my own with the children. We had two bedrooms and a sitting room and a kitchen. Outside loo and an outside coalhouse. There was a fireman, Mr Mitchell, they called him, lived three doors from us and he got the signal when he was wanted. He had to go straight to …just past Burbank Street there was a place where all the firemen were and when he got the alert we knew the air raid siren would be going any minute. So we used to get the kids, get them all ready, get the gas masks and everything and be all ready for when the siren went and then we’d run straight to the shelter and we’d sit there all night. Oh, there must have been eighty to a hundred people in those shelters. Just wooden forms all the way round and some people would lay blankets down and go to sleep, but I had two babies so I couldn’t sleep. Once when I was in this shelter, my brother was on leave and he sat with me and I felt as if I was going to pass out. I said “I’ll have to have some fresh air, I can’t breathe”. He said “come on, I’ll take you on top”. So we had to go up these steps to get out of this shelter. The warden said “where are you going? The air raids on, you know”. Then all of a sudden we heard the planes. Me brother was in the Air Force and he was listening. He said “that one’s not ours”. All of a sudden a plane swooped down and he pushed me down the stairs and he jumped down after me and the warden come in after us and managed to slam the doors shut. You could hear, it went all over the doors – he dived down and it was firing at the air raid shelter as we went in again. So that was twice I nearly had it!

If you went to the pictures and the siren went anybody who wanted could go out to the shelters. There was a shelter in Grange Road; it used to be a big field there, they called it the Bull Field and they had a big shelter on there. Those that didn’t want to they’d sit right underneath where the circle is. This one night – I never used to get out – me dad said “go on, go to the pictures, I’ll keep an eye to the kids”. Well all of a sudden it come on the screen “the siren’s just gone”, so I jumped up straight away, I wasn’t going to leave the kids with me dad. Just as I got into Stockton Street I heard this plane zooming down so I went into a shop doorway; it was a jewellery shop and I crouched right down. And all of a sudden I seen this plane and it was just like a beautiful big silver brooch and all the searchlights was on it. And it looked so beautiful. And I thought “eeh, that must be one of them, they must be going to shoot it down.” Then all of a sudden another one zoomed down and started firing at all the shop windows. And I was crouched right in the corner on the floor and all the glass windows in the shop was all shot, all smithereens and pieces. As soon as it went off I ran all the way home until I got to the house and me mother said “where have you been when they were dropping the bombs?” When I told her she said “oh, you shouldn’t have gone to the pictures”.

I kept moving around because I was frightened of the bombs and thinking I’d escape them. I went to live in Mainsforth Terrace and downstairs there was a cellar. I was in there with the two babies and there was a raid on and I was terrified and I daren’t go down the cellar because I kept hearing noises. I thought “there’s somebody gone in the cellar” and I was scared to death. I took the babies and got underneath the bed – I don’t know what I thought that would do! When he come home he went downstairs to have a look. He come back up, he said “ don’t ever go down there – it’s full of rats!” So I had to move again! I moved about half a dozen times, I was like a gypsy – one place to another.

Rations! Oh, my God, they were a headache. We didn’t have a lot of money so we couldn’t buy a lot of sweets, but we used to make a special day for the kids to have the sweets. Him being in the army, he sent me a food parcel once. There was all sorts in it. There was chocolate in for the kids and there was butter, there was even eggs in and all sorts and oh, I was over the moon! So my next-door neighbour, I helped her a bit. But that’s what you had to do, you had to help each other. I helped them all, but they helped me so it’s only fair. I used to take a coat of mine, cut it up and make trousers for my little lads and I used to do it all by hand, I didn’t have a sewing machine. Once a saw a remnant in a shop, a bit of satin and it was beautiful and it only cost coppers because it was only in pieces. It was a peach colour, and the other was very pale green with little flowers in it. So I bought it – I thought “what am I going to do with it?” So I made myself two pairs of French knickers! I showed me neighbour and everybody in the street wanted me to make them French knickers. My knickers went all the way round the street! I was knitting jumpers while I could, while you could get the wool. I used to make the hooky mats; clip mats with the old socks. I used to wash them and cut them up into little strips and take a peg and break it in half get the kids and show them how to do it. And I had all the kids helping me and I made a great big hooky mat and it was all framed black all the way round and coloured in the centre and it was lovely. But there was only one thing; it was too heavy, I couldn’t shake it. The kids had to help me.

When we were washing we used to have all our lines out in the back lane, right across from one end of the lane to the other. I’d get up at half past six in the morning to get me lines out. Then the coal man would come round with his horse and cart, they called him Tommy Burbeck, and he’d shout “Coal!” so we knew he was coming, so we’d take the sheets off and put the prop to hold them right up. But then the bin men used to come round, and their’s used to be a horse and cart and they used to just come and knock all the sheets down and everything; they didn’t care, they were really nasty. And the sheets used to always be lovely and white. We used to scrub everything. We had a big wooden tub and a big poss stick - mind we had to be strong. I had a big wooden table outside in the back yard and I’ve stood out there in the snow. I had a cape round me neck what he got in the army – it was a waterproof and he gave me it. And I would scrub everything and I would put it in the poss tub and give it a good poss and then put them through the little mangle and then put it in a copper and put all the fire underneath. The only way I used to get my copper going was I used to put old Wellingtons in and the flames used to come out the top and then the water would boil. We used to boil everything, all our clothes because although we had nothing we were spotless. I used to boil them all, then put them back in a big tub of water, poss them all again. No wonder we had big arms! Then we had to hang them on the line and try and dry them. And if we couldn’t get them dry we’d have to dry them round the fire, oh….Washday started on the morning and it was teatime before we got finished and then we were still trying to dry them round the fire. Then there was the ironing after that. The irons we used to put on the fire, I had two of them. Me dad used to work the shipyard. He used to make me pokers and shovels and all sorts. We couldn’t do any papering because you couldn’t get paper then, so we used to keep the newspapers and I used to paper the wall with newspapers and then it was called distemper, and I used to do it all nice colour, very pale colour, and then I’d go and get me husband’s shaving brush and I’d get a different colour and I’d make little marks like little roses all over. You had to improvise for everything you wanted. They were hard times, but it’s a funny thing, when the war was over you seemed to miss it, because it had been excitement as well.

When Sammy come home, of course, I had another baby. That’s what happened then, because there was no preventions, nothing like that then. So every time they come home on leave they used to always leave something behind! So I was expecting a baby and of course you couldn’t get the ambulance then, because it was all for the war; they had all the ambulances, so I had to have a taxi. And I was booked in at Grantully Nursing Home because I used to have terrible times having me babies, they were always breach babies and so the nurse said “you’ll have to go into hospital next time.” I had the first one at home and I nearly lost me life, and they said “you should have them in hospital”. The second one I had at home and I lived in Grace Street then. I had such a time, the nurse couldn’t bring the baby and in the finish she brought the baby and she said “it’s a shame, it’s a beautiful baby boy, but he’s died”. And they put him on the chair and this old lady, she was about eighty, she picked the baby up and the nurse was messing on with me because I had such a bad time and all of a sudden I heard the baby cry. The nurse said “how did you do it?” She’d been breathing into his mouth. The old woman brought him round. So this time they took me to Grantully. The air raid siren was going as we got into Grantully, and they got me in and they put me on this bed, like, and they were saying “you’ll have to try and push” – well it was a breach baby, you couldn’t do anything about it! They were trying and trying and at the finish they said “you’re not ready to have it yet” and they just left me! They went away and I was in torture. Then all of a sudden the siren went again and then they started dropping bombs so they had to get hold of me and pull me up the bed. I said “the baby’s coming!” They said “well you can’t have it now, you should have had it before” as if I had a choice in it! And so in the finish they had to stop while they were dropping the bombs, I had the baby, then they said “quick, you’ll have to get down in the cellar”. I just collapsed on the floor, I couldn’t walk. So a nurse got hold of me hand and she wrapped the baby in something and they took us all down in the cellar and they brought all the babies and they gave me a baby to hold. And then when we got back upstairs we found out I hadn’t the right baby! It was someone else’s baby – it was a little girl and mine was a little boy! After my husband come home, he said “that’s not my baby”, but when he grew up he was the image of him!

You had to pay for a doctor in those days, sixpence a week, and my poor doctor never got his sixpence. Nobody paid. Some doctors you had to, but mine was Dr Hillis, he was such a good doctor. I paid for quite a while and then I couldn’t pay much more. Me first baby, it was a nurse from Grantully who come to see me. It was a breach baby and she didn’t know anything to do. She didn’t know how to bring it, so she just sat there. And there was a neighbour with her, ever so many people, all sitting there having a cup of tea and I was under the table screaming in agony. And a neighbour went round for my doctor and he come round in his car in his pyjamas and he borrowed an apron off somebody and he give me something to knock me out. Anyhow he gradually got the baby out, and he got me in bed and he chased the nurse. He said “go back to Grantully Nursing Home and be taught how to deliver a baby.” And he come in every day till I got all right and he was really smashing. And when I went to pay he said “can you afford that? Leave it this week.” How many doctors would you find like that these days? I had four lads at the finish born during the war, and two girls born after the war.

More detail » Air Raids by John Lee

Air Raids by John Lee

In 2005 Hartlepool's Museum and Library Services worked together on a project called 'Their Past, Your Future', which commemorated the part played by local people in the Second World War. As part of the project John Lee, from the 'Writing Together' group, reminisced about his time in the messenger service. This is his story:

In December 1939 an underground report centre was established in the grounds of Grays Museum, this was the nerve centre for all civil defence operations, a hub of activity at the outbreak of war. It was here that A.R.P. messengers, drawn from the boy scouts, boys brigade and civilian population provided a service throughout the town, relaying information to the various civil defence groups.

West Hartlepool was one of the first industrial towns in the country to experience the horror of German bombs, and for Mr Lee, his first taste of enemy action. In 1940 four bombs were dropped. Two people were killed, and sixty- three injured. Over two hundred properties were destroyed or damaged. Four bombs fell at Gunners Vale Farm at Elwick. Buildings were demolished, but the farmer and seven others survived after taking refuge in a home made shelter. Mr Lee’s sister found her shop in Musgrave Street had taken a direct hit.

It was in this first raid that an air raid warden was killed by enemy action. This brave man was Mr John Punton of William Street.

The raids continued and grew in intensity. Mr Lee was witness to the fire at Tin Boxes Ltd which suffered a direct hit. Devastation spread across the town. The work of civil defence went on regardless. The attitude of the people, brave and unbending. A report in the Northern Daily Mail read:

“The quiet demeanour and cool efficiency of hundreds of A.R.P. workers, paid and unpaid men and women, not to mention all the boy messengers, was an unfailing support to public morale.”

Mr Lee recalls a particularly tragic time when three women and six children died in a bombed out cellar, despite the efforts of the demolition squads who laboured night and day to save them.

Throughout the war Mr Lee divided his time between the steel works, and the messenger service. A harsh environment existed in the steelworks. The working conditions were intolerably hot and dusty due to the blackout requirements imposed by the government. The atmosphere was laden with dust and fumes making visibility very difficult and a safety hazard.

In 1941 the house in which the grandparents of Mr Lee were sheltering was bombed. The family of seven had taken cover in a bedplace under the stairs. They were extracted from the ruins within twenty minutes. When Mr Lee arrived Grandad was sitting in an armchair in the middle of the road giving all his worldly goods away. He was obviously suffering from shock!

Thankfully the last record of air raids was made on March 22nd 1943. Ever vigilant, the work of the Civil Defence continued, until at last we could all sleep safe in our beds.

The bravery of those engaged in the defence of our country has not been forgotten.

More detail » Air Raids on the Hartlepools in World War II

Air Raids on the Hartlepools in World War II

Introduction

In the Second World War, the twin towns of Hartlepool and West Hartlepool were both victims of German air raids. Air raids on the Hartlepools took place between June 1940 and March 1943. Seventy people were killed during that time, including the first Civil Defence worker to be killed by enemy action. The two towns were both centres of heavy industry, such as shipbuilding, engineering, steelworks, and boilermaking which made them prime targets. The north-east coast of England is also near enough to Germany for it to be possible to fly a plane across the North Sea, drop explosives on a target and return home before running short of fuel.

There were forty-three raids on the two towns in total with seventy deaths, forty-eight at West Hartlepool and twenty-two at Hartlepool. Although the aim was to destroy any industry which would help the British war effort, the bombs hit houses, shops, and other buildings such as factories, churches and hotels.

The people of the Hartlepools had many warnings which did not result in a raid on the towns. West Hartlepool had 480 warnings, but there were only thirty-six raids where bombs were dropped. Many of the raids happened during night hours, and were usually carried out during the favourable weather of the summer months.

ARP (Air Raid Precautions) in the Hartlepools

ARP was initially formed before the start of the war in 1935. Preparations for protecting civilians were already in hand before the outbreak of war. By September 1938 ARP had seventy trained wardens in West Hartlepool. A few months after the outbreak of war on 3rd September 1939 the number had increased to 1500. There was a similar growth in the number of wardens in Hartlepool. ARP arrangements were thus already in place by the summer of 1940, when the raids started. The first British civil defence worker to be killed by enemy action died in West Hartlepool on 19th June, 1940. He was John Punton, aged fifty-four. He was directing other people towards the nearest air raid shelter, when a bomb fell nearby and he was killed in the blast.

Bomb damage in West Hartlepool

5745 buildings were damaged at West Hartlepool. 251 were damaged twice, nine damaged more than twice. More than a hundred buildings were completely demolished. These included the Yorkshire Penny Bank, three hotels and the offices of the West Hartlepool Greyhound Stadium.

Only seven raids caused serious damage or casualties. Three raids caused thirty-eight of the deaths. On night of 19th August 1941 twenty-three people were killed when a large mine fell in back Houghton Street and Elwick Road, also causing much property damage. There were also five people seriously injured and sixty-five slightly injured. On the night of August 29th and 30th 1940, Pilgrim Street and Hilda Street were hit. One man, three women and three children died when nineteen houses were demolished.

Bomb damage in Hartlepool