Hartlepool Sports & Leisure

Hartlepool Sports & Leisure

- Cinemas, Theatres & Dance Halls

- Musicians & Bands

- At the Seaside

- Parks & Gardens

- Caravans & Camping

- Sport

Hartlepool Transport

Hartlepool Transport

- Airfields & Aircraft

- Railways

- Buses & Commercial Vehicles

- Cars & Motorbikes

- The Ferry

- Horse drawn vehicles

A Potted History Of Hartlepool

A Potted History Of Hartlepool

- Unidentified images

- Sources of information

- Archaeology & Ancient History

- Local Government

- Printed Notices & Papers

- Aerial Photographs

- Events, Visitors & VIPs

Hartlepool Trade & Industry

Hartlepool Trade & Industry

- Trade Fairs

- Local businesses

- Iron & Steel

- Shops & Shopping

- Fishing industry

- Farming & Rural Landscape

- Pubs, Clubs & Hotels

Hartlepool Health & Education

Hartlepool Health & Education

- Schools & Colleges

- Hospitals & Workhouses

- Public Health & Utilities

- Ambulance Service

- Police Services

- Fire Services

Hartlepool People

Hartlepool People

Hartlepool Places

Hartlepool Places

Hartlepool at War

Hartlepool at War

Hartlepool Ships & Shipping

Hartlepool Ships & Shipping

Royal Navy - Second World War

Details about Royal Navy - Second World War

Hartlepool’s Royal Navy service personnel who served during the Second World War, and some of the Royal Navy warships that visited the port.

Location

Related items :

Alan Butcher - Royal Navy

Alan Butcher - Royal Navy

Donated by Mrs. Violet Butcher

Donated by Mrs. Violet ButcherAlan Butcher (Tom Butcher's brother), was born around 1926. He was conscripted into the Royal Navy during the Second World War and is believed to have served on escort duty on the Russian Convoys. He once brought home a folding umbrella, which caused quite a stir as they had not been seen before.

More detail » Ashore in New York

Ashore in New York

Donated by Mr. Andrew McCluskey

Donated by Mr. Andrew McCluskeyDated 1940

Royal Navy Stoker Thomas McCluskey on the quayside at New York, sometime in the early 1940s. It is possible the ship alongside is HMS Royal Sovereign, on which Thomas served in 1940/41, and which was engaged on Atlantic Convoy escort duty during this period.

More detail » HMS Eclipse at Hartlepool

HMS Eclipse at Hartlepool

Donated by Hartlepool Museum Service

Donated by Hartlepool Museum ServiceThe Royal navy destroyer H.M.S. Eclipse (HO8), at Hartlepool, date unknown. Built in 1934, she was mined & sunk in October 1943.

More detail » HMS Express in Dock

HMS Express in Dock

Donated by Hartlepool Museum Service

Donated by Hartlepool Museum ServiceThe Royal Navy destroyer H.M.S. Express (H61), at Hartlepool, date unknown.

H.M.S. Express was built by Swan Hunter at Wallsend and was converted for Minelaying at the outbreak of WW2. In October, 1939, she was deployed laying mines for the East Coast Barrier.

On 22nd of March, 1940, she was damaged in a collision with a minesweeping trawler and was repaired in Hartlepool.

She was also called up for the Dunkirk evacuation, rescuing 3,491 troops in total. During her last trip she sustained serious damage and had to be repaired in dock. Later in 1941 she was sent to join Force Z in Singapore and rescued 1,000 men from the sinking of HMS Repulse and HMS Prince of Wales by the Japanese.

She was eventually transferred to the Canadian Navy becoming H.M.C.S. Gatineau.

HMS Express leaving Hartlepool

HMS Express leaving Hartlepool

Donated by Hartlepool Library Service

Donated by Hartlepool Library ServiceCrowds had gathered to bid farewell to HMS Express after being repaired in Hartlepool.

HHT&N 308

More detail »

In the Navy by Don Colledge

In the Navy by Don Colledge

In 2005 Hartlepool's Museum and Library Services worked together on a project called 'Their Past, Your Future', which commemorated the part played by local people in the Second World War. As part of the project war veteran Don Colledge reminisced about his time serving in the both the Merchant and Royal Navy. This is his story, in his own words:

I was born in West Hartlepool in 1925. I started off as a Sea Cadet. I did most of my training down here and at HMS Paragon, which was at the bottom of Church Street. It is now the Royal Chambers. It’s a pub now. It used to be a pub before that and it was taken over by the Royal Navy and from there they moved to the Grand Hotel. I was what was called a Bounty boy. That’s the name of a training ship down in Worcester, and you used to go down there for a month to bring you up to speed before you went down and actually joined the Royal Navy down at HMS Collingwood in Fareham in Hampshire, near Portsmouth.

I was waiting to go in the Royal Navy through the Sea Cadets and in the meantime I joined the Merchant Navy. I joined the ship at Teesport near Middlesbrough, and we went to Dunston in the Tyne and loaded a cargo of coke to take to Huelva in Spain. On the sixth of June we were torpedoed at about five to twelve in the morning. I didn’t know anything about it. I was asleep just underneath where the torpedo struck. The carpenter came in and told me what had happened. He said “you better get yourself in the lifeboat”. I had my instructions. I had to go up to the store, near the bridge, and get some condensed milk to put in the lifeboat in case you were adrift for so long. When I got up there the steward was getting all the whisky and cigarettes and stuff. He would be on the fiddle, I suppose. Anyway, me and him were left on the boat until a sloop picked us up. We were on it for two days before we got to Gibraltar and I was on Gibraltar six weeks. They didn’t tell my mother where I was or what had happened or anything, just that the allotment (money) had stopped. I used to send her an allotment every week. But when the ship was sunk I was unemployed, so I lost my pay.

I was in the Sailors’ Home in Engineers Lane on Gibraltar, which we had quite a good time down there sunbathing and swimming in Catalan Bay. But my mother didn’t know where I was, and I got a chance to work me passage coming back. It was some menial job washing up or something like. We landed at the Clyde, and I was given half a crown expenses and a travel warrant for the train. I got to Newcastle on the Saturday night from Glasgow and I was asleep on the platform because I had missed the last train to Hartlepool. A policeman came up and he asked me what had happened? So I explained and told him I am just waiting for the first train in the morning. He took me around the corner and they used to sort the mail for Hartlepool at Newcastle, and he shouted “who’s going to Hartlepool?” and a bloke said “I am” and he said “Well, you’ve got a passenger here.” So he looked after me and got me there, and I walked in on Sunday morning and me mother said “where have you been?” I explained to her what had happened. She said “Oh I got the letter about your money, but I’ve been putting money away for you, so you’re all right.” And that was it. Plus I had just a pair of shorts on when I was picked up. That’s what we used to sleep in because it was dead warm on the ship. When I went ashore I got kitted out, and I had been home about a month when me mother got a bill for eight pound fifty for clothes, which she refused to pay. And she wrote to a magazine called the John Bull, she was a bit “bolshie” like that. Anyway it was all squashed. She said she would rather go to jail than pay.

Anyway I finally got into the Royal Navy and the pay was six shillings a fortnight. So then I couldn’t afford to send me mother an allotment. In the Merchant Navy I was getting more pay than that. Why I went into the Royal Navy I don’t know. I think it was 1942 when I joined my ship, and I had me eighteenth birthday on it up in Tobermory at the Isle of Mull. We used to do trips to St Johns, Newfoundland. That was Atlantic convoy. And we used to alternate with Gibraltar and Iceland. We were an escort on convoys. A fast convoy was seven days, a slow convoy was eleven days. Then we used to have a week in harbour after that, to get ready for sea again. The Atlantic convoy was the worst, especially the weather in winter in the mid-Atlantic. I was more bothered about bad weather than being sunk. I was a radio operator. Telegraphist they used to call us, and I’d passed all the exams to be a Warrant Tel., which is an officer.

I went to D-Day. We were right next to the Yanks, patrolling off the beaches. We used to do anti-submarine patrol round all the merchant ships that were coming in to Mulberry Harbour. But I can’t remember a thing about it. Maybes I didn’t want to remember. I blocked it out of me memory.

I was based in Iceland for nine month. We used to go up to the Arctic Circle and pick the convoys up coming from Murmansk. We were the guard ship, and there was an incident on VE night. There was nine of us escorts looking after one empty tanker which had unloaded his cargo in Reykjavik and it got sunk. I think it was one of the last ships sunk like that. We never got the submarine that sunk it. But we heard about VE-Day by a broadcast message. We went and got drunk.

More detail » In the Navy by Robert Wise

In the Navy by Robert Wise

In 1990, Royal Navy veteran Robert Wise wrote down his memories of life in the Royal Navy during the Second World War. We are grateful to Mr Wise's family for sharing them. This is Robbie's story, in his own words:

I was born 29th November 1916 at Sussex Street, West Hartlepool. Mother was Alice Louisa (nee Dobson). Father was Norman Henry Wise.

Mother probably worked as a servant in the ‘big houses’, and father was seafaring. He was in the Royal Navy during the First World War, afterwards he worked on the Docks for the North Eastern Railways, and was a Tug Skipper when he retired.

In 1919 the family moved to 37 Pelham Street, West Hartlepool. My education was at Brougham School, leaving at Christmas 1930, aged 14. During my school years I played cricket for the School and played football for the School and Town.

My first job was errand boy at H.M. Scott, high class bakers and confectionery, of 94 York Road. After four months I worked at a Ships Chandler in Victoria Terrace. At the beginning of 1932 I moved to a Garage in Raby Road owned by a Mr Cole; if I had remained in this job I could have served my time to be a motor mechanic. Incidentally, my first job, at Scott’s, earned me 6 shillings (30p) a week plus a bag of cakes, and the hours would be near to 50 over 6 days.

During the summer of 1932 I volunteered to join the Navy, doing my test and medical at Ryehill Gardens, Newcastle. I joined H.M.S. Ganges training barracks at Shotley, near Ipswich, as a 2nd class boy on 15th September 1932. I think my pay was 3 shillings (15p) per week, but we only received 6 pence (2.5p) pocket money each week, the remainder banked for us.

On ‘passing out’ in November 1933 I was drafted to H.M.S. Cornwall at Portsmouth. She was a 10,000 ton cruiser. Captain was a V.C. of the First War, Bell Davies. Cornwall sailed on 12th January 1934 for a 2 ½ year commission on the China Station.

The ship returned in July 1936. I then joined H.M.S. Excellent gunnery school in Portsmouth. Late in 1937 I commissioned H.M.S. Aurora in Portsmouth. The ship was new and built in the Portsmouth Dockyard, tonnage about 6,000 tons. Aurora carried the Flag of Home Fleet Destroyers and I was a member of the Admiral’s staff. On being promoted to Leading Seaman I reverted to a member of Aurora’s crew.

When war was declared on 3rd September 1939 our ship was patrolling somewhere between the Shetland Islands and Norway. We were in Scapa Flow on 14th October 1939 when an enemy submarine penetrated the harbour defences and sank H.M.S. Royal Oak. All ships in port scattered to sea and after a patrol we returned to Loch Ewe, a base in North West Scotland. We had arrived on Sunday 22nd October. The next day I left the ship and travelled by coach and train to H.M.S. Victory barracks at Portsmouth. We arrived p.m. Tuesday. On Wednesday morning I applied for, and was granted, a Long Weekend. I sent a telegram to Olive to arrange the wedding for Saturday 28th October. I got to Gateshead late Friday evening. The wedding took place at St Chad’s, Rawling Road, Gateshead. After the reception in a church hall we returned to West Hartlepool and spent the night at Vic and Ruby’s in Borrowdale Street. We returned to Gateshead Sunday evening and I left by train for Portsmouth in the early hours of Monday morning.

I was only a few days in Victory Barracks when I was sent to H.M.S. Excellent for an A.A. gunnery course. In December (after the Battle of the River Plate) a crew was quickly gathered together to commission H.M.S Hawkins, a cruiser of the First World War, and I was picked.

Hawkins sailed 9th January 1940 and we eventually found ourselves patrolling off the South American coast. We visited Montevideo, Buenos Aires, Rio de Janeiro and the Falkland Islands. We moved in September to Simonstown, the Naval Dockyard near Capetown. During this time we spent 235 days at sea and 21 days in harbour. I left the Hawkins and took passage home in the liner S.S. Strathnaver. The ship arrived in Liverpool during October and I then went to Portsmouth barracks.

Late November I moved to Hayling Island and joined the Combined Operations Organisation. Our base was an ex-holiday camp named Northney, the first such camp in Britain. Early December, with a landing craft crew, I went to Vospers boatyard at Southampton and collected two L.C.A.s (Landing Craft Assault). They were placed on Pickford’s road wagons and it took us three or four days to reach Greenock at the mouth of the Clyde. The craft were placed in the water and we awaited instructions. In the meantime we were billeted in the local Community Centre.

Early January 1941 we joined H.M.S Glenroy, previously a fast Merchant ship on the Far East run. It had been converted to an assault ship and on this occasion was loaded with Command Troops. We sailed, and ultimately arrived at Alexandria in Egypt (via Capetown). The troops we took disembarked and I believe they did valuable work in the Western Desert and Agean Sea.

Around Easter we embarked troops and sailed to the island of Cos (Agean Sea). Early one morning we commenced disembarkation but before it was complete we re-embarked and returned to Alexandria. Evidently the Germans were getting the upper hand in that sphere of the war. A few days later we loaded with more troops and sailed for Crete, with the intention of landing the soldiers on the beaches. An hour or so before arrival the situation on the island became critical so authority at a high level decided it was a forlorn hope to hold it, so we had to turn round and return to Alexandria.

I think it was September I left Glenroy and joined the Special Ops base camp at Kabrit (Suez Canal, point joining Big Bitter Lake with Little Bitter Lake). This camp was Stag K, but later changed name to H.M.S. Saunders. At this camp we trained both Navy and Army personnel for assault landings on open beaches. Adjoining our base was the training camp for the Long Range Desert Group, famous for their exploits in the Western Desert. They became the nucleus of the famous Special Air Service.

I believe it was January 1942 I embarked on a Fleet Oil Tanker (Derwentdale?) with L.C.M.s (Landing Craft Motors) on the hatches. We sailed for Benghazi and operated the port by unloading ships at anchorage. We had been there about 10 days when the Germans broke the Front Line and we had to evacuate. We loaded our own craft with stores and then steamed to Tobruk. Their Naval base party was evacuated back to Saunders and we, the Benghazi party, took over their duties. Tobruk became isolated and cut off, so all stores were convoyed and our job was to unload the ships as quickly as possible before the German Stuka aircraft destroyed them or chased them out to sea.

It was the practice for us Naval personnel to do three months service up the Desert and then get relieved. Around May relief arrived at Tobruk for everyone except me. It transpired the Petty Officer relieving me had got drunk in Alexandria while waiting passage. He had been held back waiting punishment and then, instead of coming to Tobruk, they sent him back to Saunders. It took about three weeks to realise that something was amiss and then my Commanding Officer signalled Saunders and asked about my relief. Subsequently a relief did arrive one evening (he took passage on a Naval Frigate escorting a convoy). My C.O. left it to me how, and when, I returned to Saunders. I decided to sail back on that same Frigate at 23:00 that same evening. That night the Germans broke through the Tobruk perimeter and by noon the Petty Officer who took my place was a prisoner of war. This was mid-June 1942.

For the next 12 months it was exercises and more exercises, taking troops in landing craft and assaulting beaches on the eastern bank of the Suez Canal. Around May 1943 I was with a platoon of Royal Marines and we toured army camps in Palestine demonstrating how to mann a L.C.A. from a ship , and how to disperse once the craft had beached. This tour was about three or four weeks. Back in Saunders I got a quick draft to join a ship (taking part in the Sicily landings). I had been sent to Alexandria for this ship, but it was at Port Said, so I missed out on that invasion. A few weeks later I was drafted home through the Mediterranean onboard a troopship.

I disembarked at Liverpool and arrived at a camp in Oulton Broads, near Lowestoft, sometime late October. Between Christmas and New Year a train took us to Arrochar and then bus to Inverary. I think I was there about four or five weeks and then down to Hayling Island.

We lived in houses and I was in charge of about 70 men and we had about twelve London river barges. These barges had been adapted to carry two Chrysler 8 engines for propulsion and the cargo carrying barges had a ramp on the stern. The idea was the barge be loaded with stores and run up the beach at high tide. When the tide receded the barge would be ‘high and dry’. Army lorries would then unload via the ramp. The next high tide the barge would float; it would then go alongside a ship and load with more stores and get on the beach with the next tide. One of the barges was fitted out as a complete bakery, another was a fresh water carrier. One was fitted out as a complete workshop. Another was a petrol carrier.

On D Day our target was Sword beach and we left the Nab Tower (spithead) at midnight the commencement of D Day. We all survived the Channel crossing and beached around 22:00 hours. For almost 12 days we fulfilled our duties, then a gale blew up and wrecked most of our craft. We could not function so it was decided to return all personnel to Hayling Island. We all got seven days leave. Having no craft we were just hanging around. Late 1944 and early 1945, large ships were being loaded with war material for the Far East war, and on the hatches they were placing landing craft. From our camp I was sending men to these ships to crew the landing craft.

Since November 1940 I had been attached to Combined Operations and late summer of 1945 I was returned to General Service and joined the Victory Barracks in Portsmouth. I was elected Vice President of the Petty Officers’ Mess and hoped to stay until demob (November 1946). Things did not turn out like that. Early December I was drafted to base party at Wilhemshaven. About July 1946 I was transferred to Hamburg. I came back to Portsmouth barracks late November and commenced leave straight away, finishing my naval engagement on 11th February 1947.

More detail »

Jack Herring - Royal Navy

Jack Herring - Royal Navy

Donated by Mr. John Brooker

Donated by Mr. John BrookerJack Herring (standing at the rear right), and some of his Royal Navy shipmates.

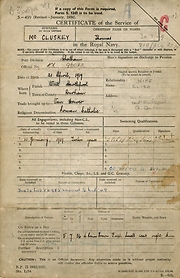

More detail » Royal Navy Certificate of Service (1)

Royal Navy Certificate of Service (1)

Donated by Mr. Andrew McCluskey

Donated by Mr. Andrew McCluskeyDated 1949

Page 1 of Thomas McCluskey's Royal Navy Certificate of Service. Thomas volunteered in January 1939 and served on a number of Royal Navy ships, including the battleships Warspite and Royal Sovereign.

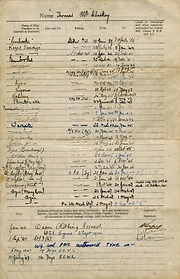

More detail » Royal Navy Certificate of Service (2)

Royal Navy Certificate of Service (2)

Donated by Mr. Andrew McCluskey

Donated by Mr. Andrew McCluskeyDated 1949

Page 2 of Thomas McCluskey's Royal Navy Certificate of Service. Thomas volunteered in January 1939 and served on a number of Royal Navy ships, including the battleships Warspite and Royal Sovereign.

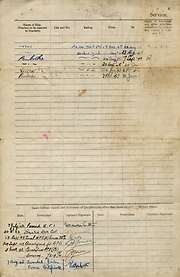

More detail » Royal Navy Certificate of Service (3)

Royal Navy Certificate of Service (3)

Donated by Mr. Andrew McCluskey

Donated by Mr. Andrew McCluskeyDated 1949

Page 3 of Thomas McCluskey's Royal Navy Certificate of Service. Thomas volunteered in January 1939 and served on a number of Royal Navy ships, including the battleships Warspite and Royal Sovereign.

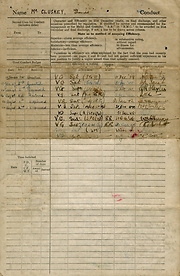

More detail » Royal Navy Certificate of Service (4)

Royal Navy Certificate of Service (4)

Donated by Mr. Andrew McCluskey

Donated by Mr. Andrew McCluskeyDated 1949

Page 4 of Thomas McCluskey's Royal Navy Certificate of Service. Thomas volunteered in January 1939 and served on a number of Royal Navy ships, including the battleships Warspite and Royal Sovereign.

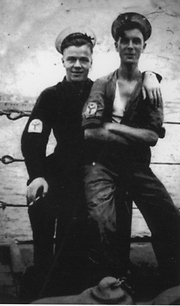

More detail » Shipmates in New York

Shipmates in New York

Donated by Mr. Andrew McCluskey

Donated by Mr. Andrew McCluskeyDated 1940

Royal Navy Stoker Thomas McCluskey (left), on board ship, probably at New York in the early 1940s.

More detail » Sinking of HMS Aldenham by Charlie Humphrey

Sinking of HMS Aldenham by Charlie Humphrey

In 2005 Hartlepool's Museum and Library Services worked together on a project called 'Their Past, Your Future', which commemorated the part played by local people in the Second World War. During the project the story of the Atherton crew’s heroic efforts at life-saving was narrated by to Bob Smith by Charlie Humphrey from Hartlepool, who, as an eighteen-year-old Ordinary Seaman, witnessed the sinking of HMS Aldenham.

Early in the morning of 14 December 1944, we left a little island called Veli Rat that had a lovely natural harbour entrance, which we more or less used as a base. We had been operating from this little place for several bombardments during that period, and usually accompanied by a couple of MTBs or MLs which used to carry the Royal Artillery FOO parties, and land them ashore for spotting purposes.

In those regions there were fairly high cliffs, and the bombarding ships used to close right in, their firing being radio-controlled by the shore parties. We arrived off the island of Pag early in the forenoon watch, and as I was not requires in the TS, I went out on the port oerlikon gun deck, as usual with a pair of binoculars. Aldenham was anchored off our port side preparing to fire, and our medical officer, who was standing near the entrance to the wheelhouse, was busy doing a sketch of her as she made a lovely sight close up against the cliffs.

By the way, both ships had anchored, and as I looked through my binoculars, I saw an old lady all dressed in black – typical peasant woman – walking along the cliff top leading a cow on a halter. As the first salvos were fired, she calmly stopped, tied up the cow and just wandered quietly away on her own, leaving the animal tethered!

With the bombardment over, both ships weighed anchor and moved out, Aldenham leading the way as she was senior, and once well clear of the area increased speed out into the open sea, the pipe went out, “Hands to defence stations.” My defence station was port oerlikon gunner for one hour and bridge lookout for the next, alternatively for four hours of the watch.

Round the time of the sinking I was standing on the oerlikon gun deck talking to my “opposite number”, a young lad the same age as myself called Geoff Grimersil, who came from Wakefield, and as it was coming in cold and started blowing up a bit, we moved over to the flag deck for more shelter.

At that moment we heard a bang, which sounded just like someone kicking a big oil drum, and Geoff said to me “What’s that, Charlie?” I said, “I don’t know but it sounded as if Aldenham had a round left in one of the guns and she was clearing it.”

With that I took a couple of steps and peered around the edge of the bridge and got the shock of my life! The Aldenham was completely blown in half, and both parts were sinking very rapidly – the fore part had turned over and was going straight down, while the after part was rising well out of the water – the screws still turning, and it looked as if the depth-charges had rolled back in their racks and broken loose.

While we were watching – completely stunned into silence, the quartermaster came out of the wheelhouse piping “Away seaboats crew, man the port seaboat”, and with us being nearest we were the first to hear the pipe. The two of us dashed down the steps to the side abreast seaboat, commenced slipping the gripes and getting ready to turn the davits out; with that the crew were scrambling into the boat. The gunner’s mate, Chief Petty Officer Wallbridge, had arrived, taken charge and suddenly found there were two crew short, so Geoff and I volunteered but were told to stand fast and assist with the lowering, and in seconds two more men jumped in, making a full crew.

The cox’n of the seaboat was a young action PO whose name I have forgotten, and with the boat lowered and slipped, it quickly pulled away searching for Aldenham survivors. There were a lot of men looking over the port side and not much that could be done there, so I made my way over to the starboard side where men were launching carley floats, tossing scrambling nets over, and even lifebelts attached to heaving lines in an effort to get some of the bobbing swimmers to the side of the ship.

As I got down near the starboard waist, I noticed a big net had been thrown over the side, and swimming towards it was a young sailor, still with a duffel coat on and an oilskin on top of it. How he swam to the Atherstone, I’ll never know, but as I assisted him inboard he asked, “Am I the only one?” I replied, “Not the only one, but I don’t think there are many.”

Seeing that he was all right, I went further aft, and right down on the scrambling net was one of our senior crew members, Bill Briden by name – a three badge AB, hanging on to a fellow, dressed in a kind of green combat jacket, who seemed absolutely all in. Looking up he called out, “Give me a hand down here, Charlie.” I climbed down, but even with our combined efforts we could not pull him up, so Bill said, “Hang on to him while I get a rope and some more assistance.”

I thought the best way to hold this man was to get close to him, slip my left arm through the holes in the net between it and the ship’s side, and hang on to his collar as hard as I could with my right hand. Anyway, while I was holding on to him, waiting for more help, the whaler came back on the starboard side which was the lee side, loaded with survivors just for’ard of where we were.

As it got alongside, the young PO cox’n put his hand on the gun’le of the boat, and with the heavy swell, I watched in horror as a the whaler took his hand right up the side of the ship and back down again. When he got his hand free, the flesh on the back of his hand was rolled back like a big flap, and all his fingers and hand bones were visible. He went off the ship to hospital with all the Aldenham wounded, but later returned as a crewmember apparently none the worse for his accident.

By then, after what seemed like ages but probably only a few minutes, Bill Briden returned with a couple of men and a rope, and as soon as the man was secured he was yanked over the guardrails to safety. It was then I noticed his legs were badly buckled, and probably broken, so it was now quite clear why he had not been able to make any effort while clinging to the safety net.

By the way he was dressed we got the impression he was one of the Aldenham’s officers, and not being able to find a stretcher for him, I dashed off for’ard in the direction of the sickbay to see what I could locate, and on returning found he had been taken down below. I never saw him again! Later on, after things had quietened down a bit, I got talking to our young Sick Berth Attendant. I asked him about the officer with the broken leg and he said, “Oh yes – he’s going to be OK.” Later it was confirmed that he was the Aldenham’s CO – Commander Farrant. The other man in the duffel coat was Able Seaman Bert West. At the time I thought it was possible we could have overlooked somebody, but for miles around the sea seemed completely empty, and it was not until dark that we proceeded to Zara to go alongside the cruiser Colombo and discharge the survivors and wounded.

Thinking back on it, I often wondered if we would have had more success in picking up survivors if we had lowered the motor boat instead of the whaler, but some months previous we had a lot of trouble in starting the engine, and if it had failed again, the boat would have been more of a hindrance than an asset.

Later on, sometime after Christmas and visiting Malta, some of the Aldenham survivors came aboard and down our messes to thank us for our efforts in saving them, and by coincidence, the chap who swam to the ship’s side in his duffel coat and oilskin was one of them. We recognised each other and to me it was rather gratifying to think I had played a small part in rescuing him.

More detail »