Hartlepool Sports & Leisure

Hartlepool Sports & Leisure

- Cinemas, Theatres & Dance Halls

- Musicians & Bands

- At the Seaside

- Parks & Gardens

- Caravans & Camping

- Sport

Hartlepool Transport

Hartlepool Transport

- Airfields & Aircraft

- Railways

- Buses & Commercial Vehicles

- Cars & Motorbikes

- The Ferry

- Horse drawn vehicles

A Potted History Of Hartlepool

A Potted History Of Hartlepool

- Unidentified images

- Sources of information

- Archaeology & Ancient History

- Local Government

- Printed Notices & Papers

- Aerial Photographs

- Events, Visitors & VIPs

Hartlepool Trade & Industry

Hartlepool Trade & Industry

- Trade Fairs

- Local businesses

- Iron & Steel

- Shops & Shopping

- Fishing industry

- Farming & Rural Landscape

- Pubs, Clubs & Hotels

Hartlepool Health & Education

Hartlepool Health & Education

- Schools & Colleges

- Hospitals & Workhouses

- Public Health & Utilities

- Ambulance Service

- Police Services

- Fire Services

Hartlepool People

Hartlepool People

Hartlepool Places

Hartlepool Places

Hartlepool at War

Hartlepool at War

Hartlepool Ships & Shipping

Hartlepool Ships & Shipping

The Army - Second World War

Details about The Army - Second World War

Army service personnel during the Second World War.

Location

Related items :

Applegarth, Frederick William

Applegarth, Frederick William

Created by unknown

Donated by Mr. Neil Wainwright

Created by unknown

Donated by Mr. Neil WainwrightFrederick William Applegarth at a Royal Artillery camp during WW2. He became Battery Sgt. Major, serving with Anti-Aircraft units using "Predictors" which helped direct the guns to track aircraft.

More detail » Applegarth, James Douglas (1)

Applegarth, James Douglas (1)

Created by unknown

Donated by Mr. Neil Wainwright

Created by unknown

Donated by Mr. Neil WainwrightJames Douglas Applegarth (on the right), with two Royal Artillery colleagues during WW2. James was attached to a Medium Regiment using Howitzers firing about 4-6 inch diameter shells.

More detail » At Dunkirk and Arnhem by Percy Fielding

At Dunkirk and Arnhem by Percy Fielding

In 2005 Hartlepool's Museum and Library Services worked together on a project called 'Their Past, Your Future', which commemorated the part played by local people in the Second World War. As part of the project war veteran Percy Fielding reminisced about his time serving in the Army. This is his story, in his own words:

I was born in Bury, Lancashire on the fifteenth of July 1920.

I was eighteen and I was in the Territorial Army, and I knew the war clouds was gathering and it was inevitable that we would go to war. And being eighteen I didn’t know if I was old enough to go to Dunkirk or not, which was our first campaign. So I kept pestering our CO and he said “by the time the war starts you will be that age so you can go”. So he was quite right, I was. I wanted to have a go you see. I was in an infantry regiment so I knew I would be involved face to face with the enemy, and I did my best to train up, especially in unarmed combat.

Before Dunkirk started we went over to Cherbourg, and it was what you call the “phoney war”. I think there was about three or four months before we kicked off. The war started on 10th May 1940, and we went into Belgium to meet the German Army. I was a Bren carrier driver. The object was to transport a Bren from one place to another under armour, so they put it in a carrier with armour round it, and I was driving it. And we had a NCO on the left and he was in charge of the machine gun – the Bren – and he could fire it as we went along. And we had a loader at the back of me that used to feed him with ammunition. The war had been on a week or two and we hadn’t made much progress, but we got to this spot and they said “right, you stay here alive or dead – you’ll stay here for twelve hours from six o’clock now till six o’clock the following morning.” You had to speak in whispers, just in case the Germans got onto you, and everything was hush-hush waiting for the Germans attacking. About 2 o’clock in the morning a big mist had come down and we heard the tramp of marching feet. I heard them first, actually and I said “I don’t think it’s the Jerries because they wouldn’t march to let you know they were here.” Well it was all stand-to, and these marching feet were coming louder and louder, so at the finish I shouted “halt”. I knew it wasn’t the Jerries, it was our own men. The Lancashire Fusiliers. A battalion had got cut off and they’d had to fight their way through and what a state they were in.

Oh, their gas capes was round here when they should have been on their back and all their faces was black. They said “keep ‘em back, lads”. I said “don’t worry lads they won’t catch you up, we’re here while six in the morning.” They gave all goodbyes and off they went. So I say that’s one thing they got out of it, they’ve fought their way out.

About ten to six the following morning nothing had transpired, and one of the lads pointed way back down the road, and they would be about two mile away. We could see them all snaking down the road, tanks and armoured cars and all that in a column. I said “well, they’re here while six o’clock spot on. If they get us it’s just too bad, but I’ll have one or two of them before they do”. Anyway it didn’t come to that. When it got to six o’clock they would be about a mile away, and they must have been tanks, because wagons would have been a lot faster. And we pushed off.

Now I am coming to Dunkirk, you see. The carrier had run out of petrol and we were surrounded and you couldn’t get food in or anything. So we got to this village and we were with a rifle company and we went into this barn to try to sleep. We were there an hour when they said the Jerries were on top of us. So we got our gear, you know, just grab anything and put it on, and we were off. So we were going down this road and we were looking for a side road, but we had passed the spot. So the officer turned the company round. This Frenchman was coming up on a bike and he shouted “arretez”. Stop, you know. I could speak French, so I got talking to him and he said there’s an ambush waiting for us down the road at the crossroads. So we turned back and kept looking for the side track, and we found it well overgrown with weeds. Nobody knew where we were going. So we sees these guards, Grenadiers, I think they were, guarding a little bridge. They said “right, you’ve got two minutes flat to get over the bridge and if there’s anybody on it it’s just too bad it’s going up”. Well we didn’t walk, we flew over it, and that’s how I found out where we were – Dunkirk. We was told after the war there was 368 000 men taken off from Dunkirk by the navy and other little craft.

So we got sorted out into three ranks and our CO said “ right, there’s a destroyer or something there, and we’re aiming for that.” We got about halfway and this shell come over and it killed three of me mates, wounded me and then wounded another two. My mate said “ you’re bleeding like a stuck pig Perc” but I couldn’t do nowt about it. You see I’d made a bad mistake. We’d got attacked in a town with what you call Stukas. They were dive bombers, you know. This girl came to me after the planes had gone, and she was pointing to her neck and she was wounded. We had been told often “do not use your shell dressing on anyone else”, but I said “oh to hell with it”, you know. So I bandaged her up. So when I got wounded I had to go about three mile along the beach to try and get on this ship. In the meantime our CO had spotted me bleeding. Anyway, he got his own shell dressing out and he bandaged me up, and I said “now what if you get wounded?” I can always remember his name, Lieutenant-Colonel Hutchinson, and he was a TA man.

And then we had to go into the bowels of the ship and the Jerries were trying to shell the ship, and it was going from side to side. But as luck would have it he didn’t hit the ship. I don’t even know yet what ship I came back on, but it was a navy ship. You’ll never find out, you see everything was confusion.

When I come back to England I was looked after by a surgeon. Took all the shrapnel out round the top of my shoulder. He said it was one inch off my jugular vein. “If it had got your jugular vein,” he said, “you would have had it.” I went from the Royal Victoria hospital in Folkestone to the Royal West Kent General in Maidstone, and then to Orpington Military Hospital. I was shunted from one to the other for about three months.

When I got patched up I went into the Parachute Regiment. I had to do all the rigmarole to pass for the Paras and I did it. It’s very tough, if you’ve got a weak spot they’ll find it. I was in the second battalion to be formed so I was one of the first, really. This guy that interviewed me said “haven’t you had enough?” I said “I’m still in uniform Sir. I’ve never had enough while I take this off.”

The major battle we had was Arnhem. We were the 6th Airborne and we had about eighteen stand-to and stand-down. Stand-to, that means you’re getting ready for battle. You’d put all your kit on, you sleep in it and everything. And when you stand-down, of course, you relax. And we got eighteen of them. We were all pig sick. At the finish they said “ right this is it” and we didn’t know where we were going but we found out when we were on the plane. And Arnhem to me was just another place. And then you know what happened at Arnhem. You had two German columns, we were about to be dropped straight on top of them. One of our lads was a Polish officer and he had an aerial photograph of Arnhem for the dropping zones, and he said “There’s armour here. You’re going to drop straight on top of it.” The officers pooh-poohed it. And we did didn’t we? We dropped straight on top of two German armoured columns – the Frundsberg and the Hohenstauften. They’d got mauled in France and had gone to Arnhem to refit.

We got dropped six miles approximately from the bridge, where we should have dropped near the bridge as possible, because paras are only lightly armed and you’ve got to be in and out. When we got three miles the Jerries were on top of us. We ran out of ammo, food and everything. You see we had moved from one place to another and where the planes thought we were they dropped all the gear, on top of the Jerries, so the Jerries got it all. 10000 people dropped and there was about 8000 got killed, wounded and taken prisoner. The Guards should have broke through and come to our rescue. We were supposed to hold the bridge for two days, and we held it for four. At the end of the second day the Guards should have come to relieve us. They were either the Coldstreams or the Grenadiers, I can’t remember now, and they didn’t get there. They were all stretched out on a single road, and they couldn’t manoeuvre round anywhere. They had to go along this road whether they were hit or not, and as soon as they got to a certain spot “woof” – the Jerries hit them and blew them apart. There was no way they could get to us. And then it was a case of every man for himself.

We left a certain number of men to keep the Jerries back and keep them guessing to think we were still there while the main body moved up to the water to get away. It was chaos pure and simple. Night time it was, and it was shotting it down with rain and we all put stuff round our feet, you know, to muffle your feet. You daren’t speak or anything and you were holding on to the bloke in front of you because it was that dark with the rain and that. And then the Jerries found out what was happening and started sending the flares over so he could see where to land his shells. I couldn’t swim so I had to get in a boat. The lads were paddling with their rifles or whatever they had to get away to the opposite side. There was about 2000 men altogether, but there wasn’t 2000 got across.

More detail » Birthday Card

Birthday Card

Donated by Frank Sherwood

Donated by Frank SherwoodBirthday Card sent to Ryder George Sherwood during the war.

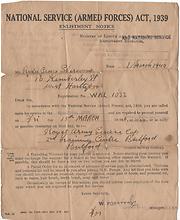

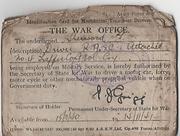

More detail » Call-Up Papers

Call-Up Papers

Donated by Frank Sherwood

Donated by Frank SherwoodCall up papers, dated 1939, for Ryder George Sherwood, 10 Kimberley Street, West Hartlepool.

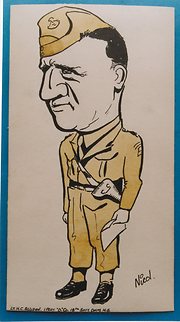

More detail » Caricature of Lt. H C Allison

Caricature of Lt. H C Allison

Created by William Nicol

Donated by Hartlepool Museum Service

Created by William Nicol

Donated by Hartlepool Museum ServiceCaricature of Lt. H C Allison by William Nicol.

Txt on drawing says "1 Plat. "D" col. 18th Batt. DHM.H.G."

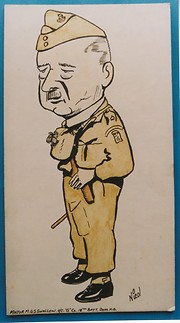

More detail » Caricature of Major M G S Swallow

Caricature of Major M G S Swallow

Created by William Nicol

Donated by Hartlepool Museum Service

Created by William Nicol

Donated by Hartlepool Museum ServiceCaricature of Major M G S Swallow by William Nicol.

Text on drawing: "O/C "G" Co. 18th Batt. DHM. H.G."

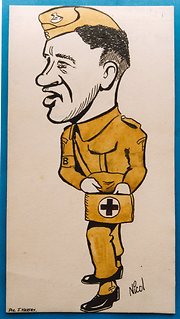

More detail » Caricature of Pte J Keesey

Caricature of Pte J Keesey

Created by William Nicol

Donated by Hartlepool Museum Service

Created by William Nicol

Donated by Hartlepool Museum ServiceCaricature of Pte J Keesey by William Nicol

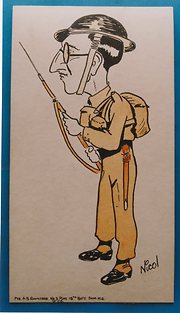

More detail » Caricature-Pte A B Rowntree

Caricature-Pte A B Rowntree

Created by William Nicol

Donated by Hartlepool Museum Service

Created by William Nicol

Donated by Hartlepool Museum ServiceCaricature-Ptc A B Rowntree by William Nicol.

Txt on drawing "No. 3 plat. "d" co. 18th Bat. DHM, H.G.

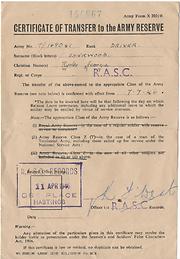

More detail » Discharge Papers

Discharge Papers

Donated by Frank Sherwood

Donated by Frank SherwoodDischarge papers for Ryder George Sherwood releasing him from the regular army into the Army Reserve.

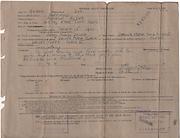

More detail » Discharge Papers (2)

Discharge Papers (2)

Donated by Frank Sherwood

Donated by Frank SherwoodAnother set of discharge papers for Ryder George Sherwood.

More detail » Discharge Papers (3)

Discharge Papers (3)

Donated by Frank Sherwood

Donated by Frank SherwoodDischarge papers for Ryder George Sherwood informing hime of his medical entitlement upon leaving the army.

More detail » Dunkirk by John Long

Dunkirk by John Long

In 2005 Hartlepool's Museum and Library Services worked together on a project called 'Their Past, Your Future', which commemorated the part played by local people in the Second World War. As part of the project war veteran John Long reminisced about his time serving in the Army. This is his story, as told to Bob Smith:

John Long was born in 1913. He had always said that he wanted to make a clean sweep of it and move to Devon when he was old enough. So, at the age of 18, he travelled from West Hartlepool to Plymouth and enlisted as a private in the 5th Wiltshire Regiment. He served overseas during the two Northwest Frontier Campaigns and a tour of Garrison duty at Tanglin Barracks in Singapore.

“I was demobbed in the early August of 1939, three weeks later I was recalled and went out on the Sunday night from Catterick Barracks, near Richmond, with the forward elements of the B.E.F.

From there we went to Armentieres, on the frontier. Then, before the German invasion began, the 15th Brigade of the 5th division was marched back to Channel ports to embark for Norway. We walked 25 miles a day for four days and then they said turn round and come back to where you come from.

So we eventually arrived in Halluine, west of Brussels and fought our first action. Then blew the bridges up and went back into France, onto the banks of the river Scarpe. The 5th Division then attacked over towards Paris, but the French never came in at the other side and they left us to it. So we got knocked about a bit. So the word came through, every man for himself, get back to Dunkirk.

By this time I was already wounded, up on the ridge of the river Scarpe. I went back into our aid post. By then we had not had much sleep, so we all slept up. It was midnight when we all woke up and it was all dead quiet. It was funny that was, then a Corporal called Smith, who laid next to me said, “John there is something wrong here.” I said, “you can tell me, where’s all the guns gone?”

So we went out, he was wounded in the arm, so he walked out and had a look. He said, “There is no one here, only us. They have all gone.” We knew how far the unit was away, as they had been in contact. So we went back on our own, me helping him along and he helping me. I had a broom under my arm for a crutch until we got to Douai. Then some company or regiment, who were also in retreat, picked us up and they left us in Armentieres.

We got treated at the Aid Station and from there we were transported in an ambulance to Dunkirk. We were on the outskirts of the Docks area and there was hundreds there. We were there for quite a while. After four days, after every boat came in and got knocked about a bit. Then they blew the mole up and we left.

We went back on the dunes. We were there another two or three days, fired on, dive bombed and shelled from inland guns. Anyway, I finally got onto a little boat, the decks swilling with water. Then I got pulled up onto a big boat and I didn’t know anymore until I got to Dover. We left a lot on the sands, all around, worse luck.

I went by train to Blackburn and was admitted to Calderstone Hospital, on the outskirts of the town. My wife came down for three days and I have a lot of telegrams from the time I was there.

When I was discharged, I was transferred to the 4th Battalion Wiltshire Regiment, as my regiment had gone to Madagascar and then onto India. One of the men who joined up with me won the Victoria Cross at Anzio.

We went ashore on D-Day plus three, as we were escorting the Mulberry harbours. I was wounded again at Caen, then we fought our way up trying to get the boys out of Arnhem. We pulled some of them across the river on boats, but not many. We lost most of the boys. We had to fight all the way up. The Germans were on three sides of us.

We lost hundreds at Caen with the 43rd Wessex Division and then got made up. Only for it to happen again. I was hit a third time, this time in the right leg and evacuated to a hospital in Kent. I never saw any of the boys who I fought with again.”

More detail » Escape from Dunkirk...and back again! by James Walker

Escape from Dunkirk...and back again! by James Walker

In 2005 Hartlepool's Museum and Library Services worked together on a project called 'Their Past, Your Future', which commemorated the part played by local people in the Second World War. As part of the project James Walker reminisced about his time serving in the Army. This is his story, in his own words:

You will understand as the years roll by a lot of things fade away in our minds but one story always stays with me. On getting to Dunkirk I had one thing on my mind and that was to get out!

I was a gunner in an anti aircraft battery. We were mobile 3.7 guns. On reaching the beaches as all this turmoil was going on I got detached from my own unit and as you may know you can always find a mate in the Army. So there were about six of us teamed up together. I remember getting to the water’s edge not noticing to worry about the time, day or what have you. I don’t know if I was ordered to go out to this little boat or volunteered but I know I was dragged in the boat by someone remembering I could not swim! Anyway we set off and thinking of home sweet home, we had not gone very far when this other boat came alongside and as it was on its way to England we soon boarded her and she set off.

I recall it was a French drifter and we found out we were the only British on board and to make things worse nobody could speak French and the French could not speak English so we were kept in the dark whatever happened. Well wet and weary, chins up and all that we didn’t care because we knew it wouldn’t be long before we would get to England. I remember checking my pockets for items. I had my pay book, my Army bible, which I got from the soldiers home in Camberly before we went over to France and I had the map Jerry had dropped telling us to surrender. I still have it now, ageing like me.

Our fully laden little drifter chugged along and at last the white cliffs of Dover came into sight. Everyone was feeling good as we had made it. Anyway, after some time we laid off the port as there were ships everywhere. I don’t recall how long we laid off there than all of a sudden we were sailing again but alas not into the port. We thought “Ah, well with too many ships in Dover we were going to some other port”. But to our dismay we were going out to sea again! Horror and disappointment came quickly. What had we to do? We could get no understanding from anyone on board! Dumbfounded! Land! Yes we sailed into France again. Le Havre!

On land we were shunted around, some to other regiments. We finally came out of France at St. Nazaire so I did get back after all to England. But then we found out that we would still not be going home for some time, so we decided we must get some contact with home and each of us started off for our home towns. One fellow was from Scotland, some from the Midlands, London etc. I was up north. On the way I sloped off where I got a lift and a very good couple took me in their house. I had a shave and a good meal and they gave me 10/- (50p) to help get me home. God bless them. I never did see them good people again. Pity.

Now you will understand all Britain was in a turmoil. I bluffed my way from Kingston-on-Thames by lorry and train. I must say I was questioned a few times on the way and when I look back I must have been a bit crafty and to think I only had my battle dress on and a tin hat! I arrived in Darlington station, got a United bus to Billingham, not one penny in my pocket and “home”! My mother was in shock for three days. Unknown to me someone had come from Dunkirk and told her I was dead!

More detail » Four Gunners

Four Gunners

Donated by Mr. Brian Ward

Donated by Mr. Brian WardFrederick Walter Ward and three other Royal Artillery gunners - Smith, Hodder and Thompson - in 1940.

More detail » Frederick Walter Ward - Royal Artillery

Frederick Walter Ward - Royal Artillery

Donated by Mr. Brian Ward

Donated by Mr. Brian WardDated 1944

A portrait photograph of Frederick Walter Ward, Royal Artillery, taken at Darjeeling (West Bengal), in 1944.

More detail » Home Guard

Home Guard

Donated by Douglas Ferriday

Donated by Douglas FerridayPart of the Hartlepool Library Service collection

This is believed to be a photograph of the Hartlepool Home Guard. So far only one person has been identified - Charlie watson (third row down, extreme left - excluding the group of four standing soldiers).

Jane Campbell has informed us that her grandfather John Moor (then Headmaster of Henry Smiths School) is seated in the front row, ninth from left.

More detail » Home Guard 1944

Home Guard 1944

Donated by Douglas Ferriday

Donated by Douglas FerridayPart of the Hartlepool Library Service collection

Picture of the Home Guard from 1944. No names known

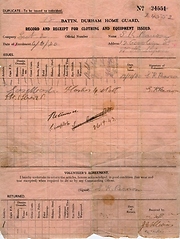

More detail » Home Guard Equipment

Home Guard Equipment

Donated by Mr. Steve Pearson

Donated by Mr. Steve PearsonDated 1940

Form issued to Steve Pearson when he joined the Hartlepool Home Guard in 1940. Steve served with the unit commanded by Major Cameron and their unit HQ was in 'Briarfields'. Mr. G. Usher was their Quartermaster.

More detail » Home Guard Greatham

Home Guard Greatham

Donated by Hartlepool Museum Service

Donated by Hartlepool Museum ServiceTypically posed group photo of Home Guard platoon from Greatham.

More detail » Home Guard at the War Memorial

Home Guard at the War Memorial

Donated by Mr. Steve Pearson

Donated by Mr. Steve PearsonA group photograph, probably of the "Gray's" Home Guards in front of the War Memorial on Victoria Road, with Sir William Gray sitting front row, centre.

HHT+N 51

More detail » Home Guard in the wet

Home Guard in the wet

Donated by Douglas Ferriday

Donated by Douglas FerridayPart of the Hartlepool Library Service collection

The Home Guard marching in the rain

More detail » John Applegarth

John Applegarth

Donated by Mr. Brian Ward

Donated by Mr. Brian WardDated 1940

A portrait photograph of John Applegarth, shortly after he was called-up in 1940.

More detail » My Army Life by Betty Brotherston

My Army Life by Betty Brotherston

In 2005 Hartlepool's Museum and Library Services worked together on a project called 'Their Past, Your Future', which commemorated the part played by local people in the Second World War. As part of the project Betty Brotherston reminisced about her time as a cook in the Army Barracks and with her husband in Japan just after the War. This is her story, in her own words:

My name is Betty Brotherston, nee Isley. I was born in June 1921, that’s a long time ago. I have heard people say “oh, the good old days”, but I don’t think they were. We had a decent upbringing, we didn’t suffer in that respect, everybody was in the same boat. I left school at fourteen and had two or three dead-end jobs. There wasn’t much work around and the work you had you got very little pocket money. I think it was a shilling a week, so I didn’t know whether to go to the dance or go to the pictures with it. There was no youth clubs, nothing. Anyway, there was three or four of us and we thought “what shall we do?” we couldn’t stay in every night. So we joined the Territorial Army, of all things. In Avenue Road, that’s where it was then. I enjoyed it. Just once a week. At that stage we didn’t do any outside activities, roughing it or going on manoeuvres, but we were took round the stores and the office and given an outline of what went on there. And we took turns on the typewriters and there was somebody teaching us, the men Territorials. I got very interested in the store work.

Then we were at the dance at the Queen’s Rink on Saturday night, September 2nd 1939 and when I came home, here’s me mother sat wringing her hands and there was this envelope “On His Majesty’s Service”. When I opened it, it was calling up papers. I had to report for duty the next day. It was at 11 o’clock that day, September 3rd, that war broke out. So we were down in the armoury for a couple of days. I remember me dad coming down and looking through the gates to see what we were doing. Then we were posted to Norton and put into a lovely house opposite a cinema. So we were having a whale of a time. We had a little bit more pocket money and during the day we just used to walk to the armoury, just a few yards from where we were billeted. Soon as we got settled in we were asked what we wanted to do. Naturally you say what you want to do, but if there’s a shortage of any particular thing they say “you can’t volunteer, it’s you, you and you!” So there was a shortage of cooks and they asked me would I go? So I said yes. I’d never done any cooking in me life, for all I was eighteen, because my mother was always there. So I’d been there a few weeks then I was called into the office and they told me I had to go down to Aldershot on a six-weeks course. Decent barracks. We had three weeks in the field kitchens and three weeks in the modern kitchens. So we got the dirty work over first, the field kitchens, because you used to come back to your billets black as coal with all the smoke and that. So I was glad that three weeks was over. Then we were put into the modern kitchens and I really enjoyed it. They were all London chefs that were teaching us so I learned quite a lot. There was three hundred men that we were cooking for.

After that they put me into the sergeants’ mess. They were horrible. The lads were all right and the officers were smashing but the sergeants! Nothing satisfied them. Once or twice a week there’d be a dance in the NAAFI. We used to work shifts; early morning till two, then two till ten, and it was my turn for the late shift and I had to make the soup. There was one particular sergeant that nobody liked – there’s always one. I said to him “look, the soup’s on and cooked. Can I leave it and go up to the dance for the last hour?” And he wouldn’t let me, he went right by the book. I was that mad about it I put too much salt in the soup for spite! They were all coming in the NAAFI ordering pints after! After that I was put into the officers’ mess and they were so nice. Once a fortnight all the officers from all the surrounding areas would come into the Headquarters and they had a seven-course dinner. I was really dreading it but the Catering Officer was Captain Carson and he was lovely, very helpful. He knew that I was new and hadn’t done it before on my own. He said “don’t worry about it, I’ll help you”. After each course he came back to see I was all right. Every time I see a banana it reminds me of him, because the sweet was fried banana with sugar on. You never saw bananas except in the army. Oh, I was glad when that night was over.

During that time in Aldershot, that’s when I met me husband, Tom. He was in the Military Police. I’d got friendly with a Scots girl, May, and we were going to the NAAFI. When we got up the bank there was these two Redcaps. One of them pulled me up and said “where’s your gasmask?” I said “well, is it necessary? We’re just going for our supper in the NAAFI round the corner. And anyway, what’s it got to do with you?” I could feel the Scots girl nudging me but I was green as grass. So he said “well, we could report you for this” and I thought “ooh, I’ve dropped a clanger, here” so I tried to be nice to them. They said they finished at nine o’clock and they would come to the NAAFI to see us. I said “please yourself” and forgot about it. Then these two chaps came in after nine o’clock and sat down with us. They didn’t have their caps on so I didn’t recognise them and thought they were being a bit pally, sitting down without being asked. It was May who told me they were the Military Police I had been cheeky to. So the few weeks that was left there we went to the pictures and we’d go for walks and that’s how it came about. I wouldn’t care, Tom was a sergeant – he knew how I felt about sergeants! So when my time finished I came back to Hutton Gate. That was a huge camp and I got a good grounding in different styles of food. The officers had not so much stodgy food as the young soldiers, you couldn’t fill them. But they got lovely steaks and everything. We were well fed, I was a tubby little thing. When I used to come home and see me mother with her bit of rations, scratting on…

Tom was posted overseas. He came back but he said “it won’t be for long, it’s on the cards that we’re off somewhere”. So we decided we’d get married. It was a quick wedding, both in uniform. I suppose if the war hadn’t have been on you would have prepared a wedding and set a date for the next year, but a lot of people just took the chance and got on with it. I came out of the army in 1941, but I enjoyed my two years in the army better than I did my civilian life, because I was doing something I liked and I was getting a bit more pay. Tom was posted to the Middle East, the Far East and he ended up in India in the finish. In the meantime I was pregnant with Olwyn – she didn’t see her dad till she was nearly three. I lived with my mother and Olwyn thought my dad was her dad. My sister was home as well, with her little one, so we were overcrowded. Tom came home in January 1945. The war finished in Japan in the August, and that’s when he went out to Japan. I got a letter to say they were letting the wives come out and they were building a little village for us. We got the papers with all this bumph, what we had to do and what we hadn’t to do, what we could take and what we couldn’t take, and that’s when I started to get a stomach ache! Oh dear, Japan! Me mother didn’t want us to go and Olwyn didn’t want to leave her nana.

Anyway, we made it. Me father took us down to King’s Cross and then we had to go to Waterloo to get the boat train, but the families weren’t allowed to go with us, so he couldn’t stand at the dock to wave us off. We were on the boat for six weeks. It was like a lovely holiday! I enjoyed it. We stopped at different ports, Egypt, Singapore, Hong Kong. There was a young man and woman. They had no family but he was going out to Shanghai to manage this factory and they took us under their wing and we went ashore with them. I don’t think I would have gone without somebody escorting me. Anyway, we got to Japan and we docked, but we couldn’t land because we were flying the Yellow Flag. It was that year that infantile paralysis was rife, 1947, and this little girl had got it. So they took her off to the nearest military hospital and we reckoned we were going to stay there in the docks for forty-eight hours. Then the next thing, I could see a police launch coming out. Somebody loaned me a pair of binoculars and I could see my husband on it. It came up to the ship and they got on, so I said “we can’t get off yet”. “Don’t I know it,” he said. “But I’m getting you off.” He went to see the Captain, and he said we could go. So we got off two days before the ship actually docked.

Our house was lovely. Two bedrooms. We had two girls, servants you know. I could have had three but I liked to do my own cooking and things. They could speak bits of English and I could pick up bits of Japanese. One of them was a war widow with a little boy. One day she had nobody to mind the little boy, so I said “bring him here”. Well what people said! They called me the soft Englishwoman. But I said “he wasn’t responsible for the war, that little boy! His father’s dead.” But apart from these two girls we didn’t mix with the local people. We had our own village with a shop we got our food from and we had BAFS (British Allied Forces) paper money. We made our own entertainment and invited people over for dinner and got the grog out. At the weekend Tom would borrow a jeep and he would take us for runs out and picnics. That was the only time we got out of the village. We were there coming up to a year and Olwyn was six and I fell pregnant. I booked into the Military hospital over there. Then we got a fortnights notice that the British wives had to go home. By then Tom had got promotion to the S.I.B., that’s the Special Investigation Branch, dealing with drugs. He was the chief witness in a case and it was proceeding when I was due to go home, so I wasn’t looking forward to coming back on my own. But it had to be done and they promised him as soon as the case finished they would fly him to the next port where the ship was, and this is what they did. So the last part of the journey we came back together.

More detail »

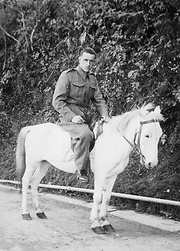

On a white charger

On a white charger

Donated by Mr. Brian Ward

Donated by Mr. Brian WardDated 1944

Frederick Walter Ward on horseback in Darjeeling (West Bengal), in 1944/45.

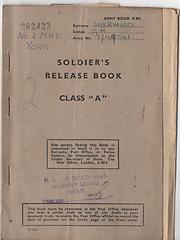

More detail » Soldiers Release Book

Soldiers Release Book

Donated by Frank Sherwood

Donated by Frank SherwoodSoldiers Release Book issued to Ryder George Sherwood.

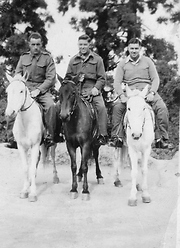

More detail » Three horsemen

Three horsemen

Donated by Mr. Brian Ward

Donated by Mr. Brian WardDated 1944

Frederick Walter Ward (Royal Artillery), and two other soldiers on horseback in Darjeeling (West Bengal), in 1944.

More detail » War Office Driving Licence

War Office Driving Licence

Donated by Frank Sherwood

Donated by Frank SherwoodWar Office Driving Licence issued to Ryder George Sherwood in 1940.

More detail » West Hartlepool Home Guard

West Hartlepool Home Guard

Donated by Hartlepool Museum Service

Donated by Hartlepool Museum Service"F" Gray's Company 18th BN Durham (West Hartlepool) Home Guard. Taken in Victory Square.

More detail » West Hartlepool Home Guard

West Hartlepool Home Guard

Donated by Hartlepool Museum Service

Donated by Hartlepool Museum ServicePhotograph of the Home guard taken in front of the world war one memorial with Avenue Road in the background. Commanding Officer was J W Cameron.

More detail » West Hartlepool Home Guard

West Hartlepool Home Guard

Donated by Hartlepool Museum Service

Donated by Hartlepool Museum ServiceGroup photo of uniformed men, with rifles. Outdoors.

More detail » West Hartlepool Home Guard

West Hartlepool Home Guard

Donated by Hartlepool Museum Service

Donated by Hartlepool Museum ServiceWest Hartlepool Home Guard marching in the rain.

More detail » West Hartlepool Home Guard despatch motorcycle riders

West Hartlepool Home Guard despatch motorcycle riders

Donated by Hartlepool Museum Service

Donated by Hartlepool Museum ServiceDespatch Riders Group 18 attached to the Home Guard, pictured on the Bull Field (now the site of the Civic Centre). To the left was the Army Barracks, which was also the Motor Transport Department (and supplied the petrol needed for the motor cycles) and the Armoury.

3rd from the Left: Stan Smith –Dirt Track Rider

5th from the Left: Geoff Saunders

14th from the Left: Charlie Dutton – Dutton’s Garage opposite Travellers Rest

1st from the Right: name unknown but he was Manager of the Staincliffe Hotel

4th from the Right: Guy Perry – Lodged at Rium Terrace. Lived in Biggleswade, became director of Convair Aircraft Company in Canada

5th from the Right: John Proudlock

8th from the Right: Don Kirkpatrick

The last 6 riders on the right were apprentices at CMEW and Richardson & Westgarths.

More detail »

West Hartlepool Home Guard despatch motorcycle riders (2)

West Hartlepool Home Guard despatch motorcycle riders (2)

Donated by Hartlepool Museum Service

Donated by Hartlepool Museum ServiceWest Hartlepool Home Guard despatch motorcycle riders in Victory Square, Hartlepool.

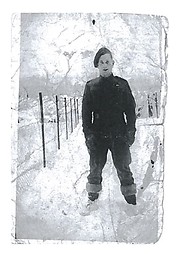

More detail » William Henry Buchan

William Henry Buchan

Donated by David Buchan

Donated by David BuchanWilliam Henry Buchan, born 7th June 1912 in West Hartlepool. He married Mary Agnes Dolan in 1947.

Little is known about William's service history, other than he did serve in Germany, Belgium, and France.

William lived most of his life in the area known as "Wagga". Later in life he lived in Dundee Road, Hartlepool. He died on 26th January 1995.

Photograph taken at Ardennes in 1945.

More detail »